THE s-BLOCK ELEMENTS (Deleted)

“The first element of alkali and alkaline earth metals differs in many respects from the other members of the group”

The s-block elements of the Periodic Table are those in which the last electron enters the outermost s-orbital. As the s-orbital can accommodate only two electrons, two groups ( 1 & 2) belong to the s-block of the Periodic Table. Group 1 of the Periodic Table consists of the elements: lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, caesium and francium. They are collectively known as the alkali metals. These are so called because they form hydroxides on reaction with water which are strongly alkaline in nature. The elements of Group 2 include beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, barium and radium. These elements with the exception of beryllium are commonly known as the alkaline earth metals. These are so called because their oxides and hydroxides are alkaline in nature and these metal oxides are found in the earth’s crust[^0].

Among the alkali metals sodium and potassium are abundant and lithium, rubidium and caesium have much lower abundances (Table 10.1). Francium is highly radioactive; its longest-lived isotope

The general electronic configuration of s-block elements is [noble gas]

Lithium and beryllium, the first elements of Group 1 and Group 2 respectively exhibit some properties which are different from those of the other members of the respective group. In these anomalous properties they resemble the second element of the following group. Thus, lithium shows similarities to magnesium and beryllium to aluminium in many of their properties. This type of diagonal similarity is commonly referred to as diagonal relationship in the periodic table. The diagonal relationship is due to the similarity in ionic sizes and /or charge/radius ratio of the elements. Monovalent sodium and potassium ions and divalent magnesium and calcium ions are found in large proportions in biological fluids. These ions perform important biological functions such as maintenance of ion balance and nerve impulse conduction.

10.1 GROUP 1 ELEMENTS: ALKALI METALS

The alkali metals show regular trends in their physical and chemical properties with the increasing atomic number. The atomic, physical and chemical properties of alkali metals are discussed below.

10.1.1 Electronic Configuration

All the alkali metals have one valence electron,

| Element | Symbol | Electronic configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium | ||

| Sodium | ||

| Potassium | ||

| Rubidium | ||

| Caesium | ||

| Francium |

10.1.2 Atomic and Ionic Radii

The alkali metal atoms have the largest sizes in a particular period of the periodic table. With increase in atomic number, the atom becomes larger. The monovalent ions

10.1.3 Ionization Enthalpy

The ionization enthalpies of the alkali metals are considerably low and decrease down the group from

10.1.4 Hydration Enthalpy

The hydration enthalpies of alkali metal ions decrease with increase in ionic sizes.

10.1.5 Physical Properties

All the alkali metals are silvery white, soft and light metals. Because of the large size, these elements have low density which increases down the group from Li to Cs. However, potassium is lighter than sodium. The melting and boiling points of the alkali metals are low indicating weak metallic bonding due to the presence of only a single valence electron in them. The alkali metals and their salts impart characteristic colour to an oxidizing flame. This is because the heat from the flame excites the outermost orbital electron to a higher energy level. When the excited electron comes back to the ground state, there is emission of radiation in the visible region as given below:

| Metal | Li | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | Crimson red |

Yellow | Violet | Red violet |

Blue |

| 670.8 | 589.2 | 766.5 | 780.0 | 455.5 |

Alkali metals can therefore, be detected by the respective flame tests and can be determined by flame photometry or atomic absorption spectroscopy. These elements when irradiated with light, the light energy absorbed may be sufficient to make an atom lose electron.

Table 10.1 Atomic and Physical Properties of the Alkali Metals

| Property | Lithium Li |

Sodium |

Potassium |

Rubidium Rb |

Caesium Cs |

Francium Fr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 3 | 11 | 19 | 37 | 55 | 87 |

| Atomic mass |

6.94 | 22.99 | 39.10 | 85.47 | 132.91 | |

| Electronic configuration |

||||||

| Ionization enthalpy |

520 | 496 | 419 | 403 | 376 | |

| Hydration enthalpy |

-506 | -406 | -330 | -310 | -276 | - |

| Metallic radius / pm |

152 | 186 | 227 | 248 | 265 | - |

| Ionic radius |

76 | 102 | 138 | 152 | 167 | |

| m.p. / K | 454 | 371 | 336 | 312 | 302 | - |

| b.p / K | 1615 | 1156 | 1032 | 961 | 944 | - |

| Density |

0.53 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 1.53 | 1.90 | - |

| Standard potentials |

-3.04 | -2.714 | -2.925 | -2.930 | -2.927 | - |

| Occurrence in lithosphere |

*ppm (part per million), ** percentage by weight;

This property makes caesium and potassium useful as electrodes in photoelectric cells.

10.1.6 Chemical Properties

The alkali metals are highly reactive due to their large size and low ionization enthalpy. The reactivity of these metals increases down the group.

(i) Reactivity towards air: The alkali metals tarnish in dry air due to the formation of their oxides which in turn react with moisture to form hydroxides. They burn vigorously in oxygen forming oxides. Lithium forms monoxide, sodium forms peroxide, the other metals form superoxides. The superoxide

In all these oxides the oxidation state of the alkali metal is +1 . Lithium shows exceptional behaviour in reacting directly with nitrogen of air to form the nitride,

10.1.7 Uses

Lithium metal is used to make useful alloys, for example with lead to make ‘white metal’ bearings for motor engines, with aluminium to make aircraft parts, and with magnesium to make armour plates. It is used in thermonuclear reactions. Lithium is also used to make electrochemical cells. Sodium is used to make a

10.2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE COMPOUNDS OF THE ALKALI METALS

All the common compounds of the alkali metals are generally ionic in nature. General characteristics of some of their compounds are discussed here.

10.2.1 Oxides and Hydroxides

On combustion in excess of air, lithium forms mainly the oxide,

The oxides and the peroxides are colourless when pure, but the superoxides are yellow or orange in colour. The superoxides are also paramagnetic. Sodium peroxide is widely used as an oxidising agent in inorganic chemistry.

10.2.2 Halides

The alkali metal halides,

The melting and boiling points always follow the trend: fluoride

10.2.3 Salts of Oxo-Acids

Oxo-acids are those in which the acidic proton is on a hydroxyl group with an oxo group attached to the same atom e.g., carbonic acid,

10.3 ANOMALOUS PROPERTIES OF LITHIUM

The anomalous behaviour of lithium is due to the : (i) exceptionally small size of its atom and ion, and (ii) high polarising power (i.e., charge/ radius ratio). As a result, there is increased covalent character of lithium compounds which is responsible for their solubility in organic solvents. Further, lithium shows diagonal relationship to magnesium which has been discussed subsequently.

10.3.1 Points of Difference between Lithium and other Alkali Metals

(i) Lithium is much harder. Its m.p. and b.p. are higher than the other alkali metals.

(ii) Lithium is least reactive but the strongest reducing agent among all the alkali metals. On combustion in air it forms mainly monoxide,

(iii)

(iv) Lithium hydrogencarbonate is not obtained in the solid form while all other elements form solid hydrogencarbonates.

(v) Lithium unlike other alkali metals forms no ethynide on reaction with ethyne.

(vi) Lithium nitrate when heated gives lithium oxide,

(vii)

10.3.2 Points of Similarities between Lithium and Magnesium

The similarity between lithium and magnesium is particularly striking and arises because of their similar sizes : atomic radii,

(i) Both lithium and magnesium are harder and lighter than other elements in the respective groups.

(ii) Lithium and magnesium react slowly with water. Their oxides and hydroxides are much less soluble and their hydroxides decompose on heating. Both form a nitride,

(iii) The oxides,

(iv) The carbonates of lithium and magnesium decompose easily on heating to form the oxides and

(v) Both

(vi) Both

10.4 SOME IMPORTANT COMPOUNDS OF SODIUM

Industrially important compounds of sodium include sodium carbonate, sodium hydroxide, sodium chloride and sodium bicarbonate. The large scale production of these compounds and their uses are described below:

Sodium Carbonate (Washing Soda),

Sodium carbonate is generally prepared by Solvay Process. In this process, advantage is taken of the low solubility of sodium hydrogencarbonate whereby it gets precipitated in the reaction of sodium chloride with ammonium hydrogencarbonate. The latter is prepared by passing

Sodium hydrogencarbonate crystal separates. These are heated to give sodium carbonate.

In this process

It may be mentioned here that Solvay process cannot be extended to the manufacture of potassium carbonate because potassium hydrogencarbonate is too soluble to be precipitated by the addition of ammonium hydrogencarbonate to a saturated solution of potassium chloride.

Properties : Sodium carbonate is a white crystalline solid which exists as a decahydrate,

Carbonate part of sodium carbonate gets hydrolysed by water to form an alkaline solution.

Uses:

(i) It is used in water softening, laundering and cleaning.

(ii) It is used in the manufacture of glass, soap, borax and caustic soda.

(iii) It is used in paper, paints and textile industries.

(iv) It is an important laboratory reagent both in qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Sodium Chloride,

The most abundant source of sodium chloride is sea water which contains 2.7 to

Sodium chloride melts at

Uses :

(i) It is used as a common salt or table salt for domestic purpose.

(ii) It is used for the preparation of

Sodium Hydroxide (Caustic Soda),

Sodium hydroxide is generally prepared commercially by the electrolysis of sodium chloride in Castner-Kellner cell. A brine solution is electrolysed using a mercury cathode and a carbon anode. Sodium metal discharged at the cathode combines with mercury to form sodium amalgam. Chlorine gas is evolved at the anode.

Cathode:

Anode :

The amalgam is treated with water to give sodium hydroxide and hydrogen gas.

Sodium hydroxide is a white, translucent solid. It melts at

Uses: It is used in (i) the manufacture of soap, paper, artificial silk and a number of chemicals, (ii) in petroleum refining, (iii) in the purification of bauxite, (iv) in the textile industries for mercerising cotton fabrics, (v) for the preparation of pure fats and oils, and (vi) as a laboratory reagent.

Sodium Hydrogencarbonate (Baking Soda),

Sodium hydrogencarbonate is known as baking soda because it decomposes on heating to generate bubbles of carbon dioxide (leaving holes in cakes or pastries and making them light and fluffy).

Sodium hydrogencarbonate is made by saturating a solution of sodium carbonate with carbon dioxide. The white crystalline powder of sodium hydrogencarbonate, being less soluble, gets separated out.

Sodium hydrogencarbonate is a mild antiseptic for skin infections. It is used in fire extinguishers.

10.5 BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF SODIUM AND POTASSIUM

A typical

Sodium ions are found primarily on the outside of cells, being located in blood plasma and in the interstitial fluid which surrounds the cells. These ions participate in the transmission of nerve signals, in regulating the flow of water across cell membranes and in the transport of sugars and amino acids into cells. Sodium and potassium, although so similar chemically, differ quantitatively in their ability to penetrate cell membranes, in their transport mechanisms and in their efficiency to activate enzymes. Thus, potassium ions are the most abundant cations within cell fluids, where they activate many enzymes, participate in the oxidation of glucose to produce ATP and, with sodium, are responsible for the transmission of nerve signals.

There is a very considerable variation in the concentration of sodium and potassium ions found on the opposite sides of cell membranes. As a typical example, in blood plasma, sodium is present to the extent of

10.6 GROUP 2 ELEMENTS : ALKALINE EARTH METALS

The group 2 elements comprise beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, barium and radium. They follow alkali metals in the periodic table. These (except beryllium) are known as alkaline earth metals. The first element beryllium differs from the rest of the members and shows diagonal relationship to aluminium. The atomic and physical properties of the alkaline earth metals are shown in Table 10.2.

10.6.1 Electronic Configuration

These elements have two electrons in the

| Element | Symbol | Electronic configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Beryllium | ||

| Magnesium | ||

| Calcium | ||

| Strontium | ||

| Barium | ||

| Radium | Ra |

10.6.2 Atomic and Ionic Radii

The atomic and ionic radii of the alkaline earth metals are smaller than those of the

Table 10.2 Atomic and Physical Properties of the Alkaline Earth Metals

| Property | Beryllium Be |

Magnesium Mg |

Calcium Ca |

Strontium |

Barium Ba |

Radium Ra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 4 | 12 | 20 | 38 | 56 | 88 |

| Atomic mass |

9.01 | 24.31 | 40.08 | 87.62 | 137.33 | 226.03 |

| Electronic configuration |

||||||

| Ionization enthalpy (I) / kJ mol |

899 | 737 | 590 | 549 | 503 | 509 |

| Ionization enthalpy (II) |

1757 | 1450 | 1145 | 1064 | 965 | 979 |

| Hydration enthalpy (kJ/mol) |

-2494 | -1921 | -1577 | -1443 | -1305 | - |

| Metallic radius / pm |

111 | 160 | 197 | 215 | 222 | - |

| Ionic radius |

31 | 72 | 100 | 118 | 135 | 148 |

| m.p. / K | 1560 | 924 | 1124 | 1062 | 1002 | 973 |

| b.p / K | 2745 | 1363 | 1767 | 1655 | 2078 | |

| Density / |

1.84 | 1.74 | 1.55 | 2.63 | 3.59 | |

| Standard potential |

-1.97 | -2.36 | -2.84 | -2.89 | -2.92 | -2.92 |

| Occurrence in lithosphere |

390 * |

*ppm (part per million); ** percentage by weight

corresponding alkali metals in the same periods. This is due to the increased nuclear charge in these elements. Within the group, the atomic and ionic radii increase with increase in atomic number.

10.6.3 Ionization Enthalpies

The alkaline earth metals have low ionization enthalpies due to fairly large size of the atoms. Since the atomic size increases down the group, their ionization enthalpy decreases (Table 10.2). The first ionisation enthalpies of the alkaline earth metals are higher than those of the corresponding Group 1 metals. This is due to their small size as compared to the corresponding alkali metals. It is interesting to note that the second ionisation enthalpies of the alkaline earth metals are smaller than those of the corresponding alkali metals.

10.6.4 Hydration Enthalpies

Like alkali metal ions, the hydration enthalpies of alkaline earth metal ions decrease with increase in ionic size down the group.

The hydration enthalpies of alkaline earth metal ions are larger than those of alkali metal ions. Thus, compounds of alkaline earth metals are more extensively hydrated than those of alkali metals, e.g.,

10.6.5 Physical Properties

The alkaline earth metals, in general, are silvery white, lustrous and relatively soft but harder than the alkali metals. Beryllium and magnesium appear to be somewhat greyish. The melting and boiling points of these metals are higher than the corresponding alkali metals due to smaller sizes. The trend is, however, not systematic. Because of the low ionisation enthalpies, they are strongly electropositive in nature. The electropositive character increases down the group from

10.6.6 Chemical Properties

The alkaline earth metals are less reactive than the alkali metals. The reactivity of these elements increases on going down the group.

(i) Reactivity towards air and water: Beryllium and magnesium are kinetically inert to oxygen and water because of the formation of an oxide film on their surface. However, powdered beryllium burns brilliantly on ignition in air to give

(ii) Reactivity towards the halogens: All the alkaline earth metals combine with halogen at elevated temperatures forming their halides.

Thermal decomposition of

(iii) Reactivity towards hydrogen: All the elements except beryllium combine with hydrogen upon heating to form their hydrides,

(iv) Reactivity towards acids: The alkaline earth metals readily react with acids liberating dihydrogen.

(v) Reducing nature: Like alkali metals, the alkaline earth metals are strong reducing agents. This is indicated by large negative values of their reduction potentials (Table 10.2). However their reducing power is less than those of their corresponding alkali metals. Beryllium has less negative value compared to other alkaline earth metals. However, its reducing nature is due to large hydration energy associated with the small size of

(vi) Solutions in liquid ammonia: Like alkali metals, the alkaline earth metals dissolve in liquid ammonia to give deep blue black solutions forming ammoniated ions.

From these solutions, the ammoniates,

10.6.7 Uses

Beryllium is used in the manufacture of alloys. Copper-beryllium alloys are used in the preparation of high strength springs. Metallic beryllium is used for making windows of X-ray tubes. Magnesium forms alloys with aluminium, zinc, manganese and tin. Magnesium-aluminium alloys being light in mass are used in air-craft construction. Magnesium (powder and ribbon) is used in flash powders and bulbs, incendiary bombs and signals. A suspension of magnesium hydroxide in water (called milk of magnesia) is used as antacid in medicine. Magnesium carbonate is an ingredient of toothpaste. Calcium is used in the extraction of metals from oxides which are difficult to reduce with carbon. Calcium and barium metals, owing to their reactivity with oxygen and nitrogen at elevated temperatures, have often been used to remove air from vacuum tubes. Radium salts are used in radiotherapy, for example, in the treatment of cancer.

10.7 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF COMPOUNDS OF THE ALKALINE EARTH METALS

The dipositive oxidation state

(i) Oxides and Hydroxides: The alkaline earth metals burn in oxygen to form the monoxide, MO which, except for BeO, have rock-salt structure. The BeO is essentially covalent in nature. The enthalpies of formation of these oxides are quite high and consequently they are very stable to heat.

The solubility, thermal stability and the basic character of these hydroxides increase with increasing atomic number from

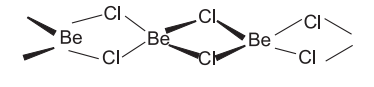

(ii) Halides: Except for beryllium halides, all other halides of alkaline earth metals are ionic in nature. Beryllium halides are essentially covalent and soluble in organic solvents. Beryllium chloride has a chain structure in the solid state as shown below:

In the vapour phase

(iii) Salts of Oxoacids: The alkaline earth metals also form salts of oxoacids. Some of these are :

Carbonates: Carbonates of alkaline earth metals are insoluble in water and can be precipitated by addition of a sodium or ammonium carbonate solution to a solution of a soluble salt of these metals. The solubility of carbonates in water decreases as the atomic number of the metal ion increases. All the carbonates decompose on heating to give carbon dioxide and the oxide. Beryllium carbonate is unstable and can be kept only in the atmosphere of

Sulphates: The sulphates of the alkaline earth metals are all white solids and stable to heat.

Nitrates: The nitrates are made by dissolution of the carbonates in dilute nitric acid. Magnesium nitrate crystallises with six molecules of water, whereas barium nitrate crystallises as the anhydrous salt. This again shows a decreasing tendency to form hydrates with increasing size and decreasing hydration enthalpy. All of them decompose on heating to give the oxide like lithium nitrate.

10.8 ANOMALOUS BEHAVIOUR OF BERYLLIUM

Beryllium, the first member of the Group 2 metals, shows anomalous behaviour as compared to magnesium and rest of the members. Further, it shows diagonal relationship to aluminium which is discussed subsequently.

(i) Beryllium has exceptionally small atomic and ionic sizes and thus does not compare well with other members of the group. Because of high ionisation enthalpy and small size it forms compounds which are largely covalent and get easily hydrolysed.

(ii) Beryllium does not exhibit coordination number more than four as in its valence shell there are only four orbitals. The remaining members of the group can have a coordination number of six by making use of

10.8.1 Diagonal Relationship between Beryllium and Aluminium

The ionic radius of

(i) Like aluminium, beryllium is not readily attacked by acids because of the presence of an oxide film on the surface of the metal.

(ii) Beryllium hydroxide dissolves in excess of alkali to give a beryllate ion,

(iii) The chlorides of both beryllium and aluminium have

(iv) Beryllium and aluminium ions have strong tendency to form complexes,

10.9 SOME IMPORTANT COMPOUNDS OF CALCIUM

Important compounds of calcium are calcium oxide, calcium hydroxide, calcium sulphate, calcium carbonate and cement. These are industrially important compounds. The large scale preparation of these compounds and their uses are described below.

Calcium Oxide or Quick Lime,

It is prepared on a commercial scale by heating limestone

The carbon dioxide is removed as soon as it is produced to enable the reaction to proceed to completion.

Calcium oxide is a white amorphous solid. It has a melting point of

The addition of limited amount of water breaks the lump of lime. This process is called slaking of lime. Quick lime slaked with soda gives solid sodalime. Being a basic oxide, it combines with acidic oxides at high temperature.

Uses:

(i) It is an important primary material for manufacturing cement and is the cheapest form of alkali.

(ii) It is used in the manufacture of sodium carbonate from caustic soda.

(iii) It is employed in the purification of sugar and in the manufacture of dye stuffs.

Calcium Hydroxide (Slaked lime),

It is a white amorphous powder. It is sparingly soluble in water. The aqueous solution is known as lime water and a suspension of slaked lime in water is known as milk of lime.

When carbon dioxide is passed through lime water it turns milky due to the formation of calcium carbonate.

On passing excess of carbon dioxide, the precipitate dissolves to form calcium hydrogencarbonate.

Milk of lime reacts with chlorine to form hypochlorite, a constituent of bleaching powder.

Uses:

(i) It is used in the preparation of mortar, a building material. (ii) It is used in white wash due to its disinfectant nature.

(iii) It is used in glass making, in tanning industry, for the preparation of bleaching powder and for purification of sugar.

Calcium Carbonate,

Calcium carbonate occurs in nature in several forms like limestone, chalk, marble etc. It can be prepared by passing carbon dioxide through slaked lime or by the addition of sodium carbonate to calcium chloride.

Excess of carbon dioxide should be avoided since this leads to the formation of water soluble calcium hydrogencarbonate.

Calcium carbonate is a white fluffy powder. It is almost insoluble in water. When heated to

It reacts with dilute acid to liberate carbon dioxide.

Uses:

It is used as a building material in the form of marble and in the manufacture of quick lime. Calcium carbonate along with magnesium carbonate is used as a flux in the extraction of metals such as iron. Specially precipitated

Calcium Sulphate (Plaster of Paris),

It is a hemihydrate of calcium sulphate. It is obtained when gypsum,

Above

It has a remarkable property of setting with water. On mixing with an adequate quantity of water it forms a plastic mass that gets into a hard solid in 5 to 15 minutes.

Uses:

The largest use of Plaster of Paris is in the building industry as well as plasters. It is used for immoblising the affected part of organ where there is a bone fracture or sprain. It is also employed in dentistry, in ornamental work and for making casts of statues and busts.

Cement: Cement is an important building material. It was first introduced in England in 1824 by Joseph Aspdin. It is also called Portland cement because it resembles with the natural limestone quarried in the Isle of Portland, England.

Cement is a product obtained by combining a material rich in lime,

The raw materials for the manufacture of cement are limestone and clay. When clay and lime are strongly heated together they fuse and react to form ‘cement clinker’. This clinker is mixed with

Setting of Cement: When mixed with water, the setting of cement takes place to give a hard mass. This is due to the hydration of the molecules of the constituents and their rearrangement. The purpose of adding gypsum is only to slow down the process of setting of the cement so that it gets sufficiently hardened.

Uses: Cement has become a commodity of national necessity for any country next to iron and steel. It is used in concrete and reinforced concrete, in plastering and in the construction of bridges, dams and buildings.

10.10 BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF MAGNESIUM AND CALCIUM

An adult body contains about

All enzymes that utilise ATP in phosphate transfer require magnesium as the cofactor. The main pigment for the absorption of light in plants is chlorophyll which contains magnesium. About

Summary

The s-Block of the periodic table constitutes Group1 (alkali metals) and Group 2 (alkaline earth metals). They are so called because their oxides and hydroxides are alkaline in nature. The alkali metals are characterised by one s-electron and the alkaline earth metals by two

There is a regular trend in the physical and chemical properties of the alkali metal with increasing atomic numbers. The atomic and ionic sizes increase and the ionization enthalpies decrease systematically down the group. Somewhat similar trends are observed among the properties of the alkaline earth metals.

The first element in each of these groups, lithium in Group 1 and beryllium in Group 2 shows similarities in properties to the second member of the next group. Such similarities are termed as the ‘diagonal relationship’ in the periodic table. As such these elements are anomalous as far as their group characteristics are concerned.

The alkali metals are silvery white, soft and low melting. They are highly reactive. The compounds of alkali metals are predominantly ionic. Their oxides and hydroxides are soluble in water forming strong alkalies. Important compounds of sodium includes sodium carbonate, sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide and sodium hydrogencarbonate. Sodium hydroxide is manufactured by Castner-Kellner process and sodium carbonate by Solvay process.

The chemistry of alkaline earth metals is very much like that of the alkali metals. However, some differences arise because of reduced atomic and ionic sizes and increased cationic charges in case of alkaline earth metals. Their oxides and hydroxides are less basic than the alkali metal oxides and hydroxides. Industrially important compounds of calcium include calcium oxide (lime), calcium hydroxide (slaked lime), calcium sulphate (Plaster of Paris), calcium carbonate (limestone) and cement. Portland cement is an important constructional material. It is manufactured by heating a pulverised mixture of limestone and clay in a rotary kiln. The clinker thus obtained is mixed with some gypsum

Monovalent sodium and potassium ions and divalent magnesium and calcium ions are found in large proportions in biological fluids. These ions perform important biological functions such as maintenance of ion balance and nerve impulse conduction.