Unit 7 The P Block Elements

In Class XI, you have learnt that the $p$-block elements are placed in groups 13 to 18 of the periodic table. Their valence shell electronic configuration is $n s^{2} n p^{1-6}$ (except He which has $1 \mathrm{~s}^{2}$ configuration). The properties of $p$-block elements like that of others are greatly influenced by atomic sizes, ionisation enthalpy, electron gain enthalpy and electronegativity. The absence of $d-$ orbitals in second period and presence of $d$ or $d$ and $f$ orbitals in heavier elements (starting from third period onwards) have significant effects on the properties of elements. In addition, the presence of all the three types of elements; metals, metalloids and non-metals bring diversification in chemistry of these elements.

Having learnt the chemistry of elements of Groups 13 and 14 of the $p$-block of periodic table in Class XI, you will learn the chemistry of the elements of subsequent groups in this Unit.

7.1 Group 15 Elements

Group 15 includes nitrogen, phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, bismuth and moscovium. As we go down the group, there is a shift from nonmetallic to metallic through metalloidic character. Nitrogen and phosphorus are non-metals, arsenic and antimony metalloids, bismuth and moscovium are typical metals.

7.1.1 Occurrence

Molecular nitrogen comprises $78 %$ by volume of the atmosphere. In the earth’s crust, it occurs as sodium nitrate, $\mathrm{NaNO_3}$ (called Chile saltpetre) and potassium nitrate (Indian saltpetre). It is found in the form of proteins in plants and animals. Phosphorus occurs in minerals of the apatite family, $\mathrm{Ca_9}\left(\mathrm{PO_4}\right)_6$. $\mathrm{CaX_2}(\mathrm{X}=\mathrm{F}, \mathrm{Cl}$ or $\mathrm{OH})$ (e.g., fluorapatite $\left.\mathrm{Ca_9} \left(\mathrm{PO_4}\right)_6 \cdot \mathrm{CaF_2}\right.$) which are the main components of phosphate rocks. Phosphorus is an essential constituent of animal and plant matter. It is present in bones as well as in living cells. Phosphoproteins are present in milk and eggs. Arsenic, antimony and bismuth are found mainly as sulphide minerals. Here, except for moscovium, important atomic and physical properties of other elements of this group along with their electronic configurations are given in Table 7.1.

Trends of some of the atomic, physical and chemical properties of the group are discussed below.

7.1.2 Electronic Configuration

The valence shell electronic configuration of these elements is ns2np3. The s orbital in these elements is completely filled and p orbitals are half-filled, making their electronic configuration extra stable.

7.1.3 Atomic and Ionic Radii

Covalent and ionic (in a particular state) radii increase in size down the group. There is a considerable increase in covalent radius from N to P. However, from As to Bi only a small increase in covalent radius is observed. This is due to the presence of completely filled d and/or f orbitals in heavier members.

7.1.4 Ionisation Enthalpy

Ionisation enthalpy decreases down the group due to gradual increase in atomic size. Because of the extra stable half-filled $p$ orbitals electronic configuration and smaller size, the ionisation enthalpy of the group 15 elements is much greater than that of group 14 elements in the corresponding periods. The order of successive ionisation enthalpies, as expected is $\Delta_{i} \mathrm{H_1}<\Delta_{i} \mathrm{H_2}<\Delta_{i} \mathrm{H_3}$ (Table 7.1).

7.1.5 Electronegativity

The electronegativity value, in general, decreases down the group with increasing atomic size. However, amongst the heavier elements, the difference is not that much pronounced.

7.1.6 Physical Properties

All the elements of this group are polyatomic. Dinitrogen is a diatomic gas while all others are solids. Metallic character increases down the group. Nitrogen and phosphorus are non-metals, arsenic and antimony metalloids and bismuth is a metal. This is due to decrease in ionisation enthalpy and increase in atomic size. The boiling points, in general, increase from top to bottom in the group but the melting point increases upto arsenic and then decreases upto bismuth. Except nitrogen, all the elements show allotropy.

7.1.7 Chemical Properties

Oxidation states and trends in chemical reactivity

The common oxidation states of these elements are $-3,+3$ and +5 . The tendency to exhibit -3 oxidation state decreases down the group due to increase in size and metallic character. In fact last member of the group, bismuth hardly forms any compound in -3 oxidation state. The stability of +5 oxidation state decreases down the group. The only well characterised $\mathrm{Bi}(\mathrm{V})$ compound is $\mathrm{BiF_5}$. The stability of +5 oxidation state decreases and that of +3 state increases (due to inert pair effect) down the group. Nitrogen exhibits $+1,+2,+4$ oxidation states also when it reacts with oxygen. Phosphorus also shows +1 and +4 oxidation states in some oxoacids. In the case of nitrogen, all oxidation states from +1 to +4 tend to disproportionate in acid solution. For example

$$ 3 \mathrm{HNO_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{HNO_3}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+2 \mathrm{NO} $$

Similarly, in case of phosphorus nearly all intermediate oxidation states disproportionate into +5 and –3 both in alkali and acid. However +3 oxidation state in case of arsenic, antimony and bismuth becomes increasingly stable with respect to disproportionation.

Nitrogen is restricted to a maximum covalency of 4 since only four (one $s$ and three $p$ ) orbitals are available for bonding. The heavier elements have vacant $d$ orbitals in the outermost shell which can be used for bonding (covalency) and hence, expand their covalence as in $\mathrm{PF_6}^{-}$.

Anomalous properties of nitrogen

Nitrogen differs from the rest of the members of this group due to its small size, high electronegativity, high ionisation enthalpy and non-availability of $d$ orbitals. Nitrogen has unique ability to form $p \pi-p \pi$ multiple bonds with itself and with other elements having small size and high electronegativity (e.g., C, O). Heavier elements of this group do not form $p \pi-p \pi$ bonds as their atomic orbitals are so large and diffuse that they cannot have effective overlapping. Thus, nitrogen exists as a diatomic molecule with a triple bond (one $s$ and two $p$ ) between the two atoms. Consequently, its bond enthalpy $\left(941.4 \mathrm{~kJ} \mathrm{~mol}^{-1}\right)$ is very high. On the contrary, phosphorus, arsenic and antimony form single bonds as $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{P}, \mathrm{As}-\mathrm{As}$ and $\mathrm{Sb}-\mathrm{Sb}$ while bismuth forms metallic bonds in elemental state. However, the single $\mathrm{N}-\mathrm{N}$ bond is weaker than the single $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{P}$ bond because of high interelectronic repulsion of the non-bonding electrons, owing to the small bond length. As a result the catenation tendency is weaker in nitrogen. Another factor which affects the chemistry of nitrogen is the absence of $d$ orbitals in its valence shell. Besides restricting its covalency to four, nitrogen cannot form $d \pi-p \pi$ bond as the heavier elements can e.g., $\mathrm{R_3} \mathrm{P}=\mathrm{O}$ or $\mathrm{R_3} \mathrm{P}=\mathrm{CH_2}\mathrm{R}=$ alkyl group. Phosphorus and arsenic can form $\boldsymbol{d} \pi-\boldsymbol{d} \pi$ bond also with transition metals when their compounds like $\mathrm{P}\left(\mathrm{C_2} \mathrm{H_5}\right)_{3}$ and $\mathrm{As}\left(\mathrm{C_6} \mathrm{H_5}\right)_3$ act as ligands.

(i) Reactivity towards hydrogen: All the elements of Group 15 form hydrides of the type $\mathrm{EH_3}$ where $\mathrm{E}=\mathrm{N}, \mathrm{P}, \mathrm{As}, \mathrm{Sb}$ or $\mathrm{Bi}$. Some of the properties of these hydrides are shown in Table 7.2. The hydrides show regular gradation in their properties. The stability of hydrides decreases from $\mathrm{NH_3}$ to $\mathrm{BiH_3}$ which can be observed from their bond dissociation enthalpy. Consequently, the reducing character of the hydrides increases. Ammonia is only a mild reducing agent while $\mathrm{BiH_3}$ is the strongest reducing agent amongst all the hydrides. Basicity also decreases in the order $\mathrm{NH_3}>\mathrm{PH_3}>\mathrm{AsH_3}>\mathrm{SbH_3} \geq \mathrm{BiH_3}$.

Table 7.2: Properties of Hydrides of Group 15 Elements

| Property | $\mathrm{NH_3}$ | PH $_{3}$ | AsH $_{3}$ | SbH $_{3}$ | BiH $_{3}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting point/K | 195.2 | 139.5 | 156.7 | 185 | - |

| Boiling point/K | 238.5 | 185.5 | 210.6 | 254.6 | 290 |

| (E-H) Distance/pm | 101.7 | 141.9 | 151.9 | 170.7 | - |

| HEH angle (') | 107.8 | 93.6 | 91.8 | 91.3 | - |

| $\Delta_{f} H^{\ominus} / \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | -46.1 | 13.4 | 66.4 | 145.1 | 278 |

| $\Delta_{\text {diss }} \mathrm{H}^{\ominus}(\mathrm{E}-\mathrm{H}) / \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 389 | 322 | 297 | 255 | - |

(ii) Reactivity towards oxygen: All these elements form two types of oxides: $\mathrm{E_2} \mathrm{O_3}$ and $\mathrm{E_2} \mathrm{O_5}$. The oxide in the higher oxidation state of the element is more acidic than that of lower oxidation state. Their acidic character decreases down the group. The oxides of the type $\mathrm{E_2} \mathrm{O_3}$ of nitrogen and phosphorus are purely acidic, that of arsenic and antimony amphoteric and those of bismuth predominantly basic.

(iii) Reactivity towards halogens: These elements react to form two series of halides: $\mathrm{EX_3}$ and $\mathrm{EX_5}$. Nitrogen does not form pentahalide due to non-availability of the $d$ orbitals in its valence shell. Pentahalides are more covalent than trihalides. All the trihalides of these elements except those of nitrogen are stable. In case of nitrogen, only $\mathrm{NF_3}$ is known to be stable. Trihalides except $\mathrm{BiF_3}$ are predominantly covalent in nature.

(iv) Reactivity towards metals: All these elements react with metals to form their binary compounds exhibiting -3 oxidation state, such as, $\mathrm{Ca_3} \mathrm{~N_2}$ (calcium nitride) $\mathrm{Ca_3} \mathrm{P_2}$ (calcium phosphide), $\mathrm{Na_3} \mathrm{As_2}$ (sodium arsenide), $\mathrm{Zn_3} \mathrm{Sb_2}$ (zinc antimonide) and $\mathrm{Mg_3} \mathrm{Bi_2}$ (magnesium bismuthide).

Answer

As we move down a group, the atomic size increases and the stability of the hydrides of group 15 elements decreases. Since the stability of hydrides decreases on moving from $\mathrm{NH_3}$ to $\mathrm{BiH_3}$, the reducing character of the hydrides increases on moving from $\mathrm{NH_3}$ to $\mathrm{BiH_3}$.

7.2 Dinitrogen

Preparation

Dinitrogen is produced commercially by the liquefaction and fractional distillation of air. Liquid dinitrogen (b.p. $77.2 \mathrm{~K}$ ) distils out first leaving behind liquid oxygen (b.p. $90 \mathrm{~K}$ ).

In the laboratory, dinitrogen is prepared by treating an aqueous solution of ammonium chloride with sodium nitrite.

$$ \mathrm{NH_4} \mathrm{CI}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{NaNO_2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{N_2}(\mathrm{~g})+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})+\mathrm{NaCl}(\mathrm{aq}) $$

Small amounts of $\mathrm{NO}$ and $\mathrm{HNO_3}$ are also formed in this reaction; these impurities can be removed by passing the gas through aqueous sulphuric acid containing potassium dichromate. It can also be obtained by the thermal decomposition of ammonium dichromate.

$$ \left(\mathrm{NH_4}\right)_{2} \mathrm{Cr_2} \mathrm{O_7} \xrightarrow{\text { Heat }} \mathrm{N_2}+4 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+\mathrm{Cr_2} \mathrm{O_3} $$

Very pure nitrogen can be obtained by the thermal decomposition of sodium or barium azide.

$$ \mathrm{Ba}\left(\mathrm{N_3}\right)_{2} \rightarrow \mathrm{Ba}+3 \mathrm{~N_2} $$

Properties

Dinitrogen is a colourless, odourless, tasteless and non-toxic gas. Nitrogen atom has two stable isotopes: ${ }^{14} \mathrm{~N}$ and ${ }^{15} \mathrm{~N}$. It has a very low solubility in water $\left(23.2 \mathrm{~cm}^{3}\right.$ per litre of water at $273 \mathrm{~K})$ and 1 bar pressure and low freezing and boiling points (Table 7.1).

Dinitrogen is rather inert at room temperature because of the high bond enthalpy of $\mathrm{N} \equiv \mathrm{N}$ bond. Reactivity, however, increases rapidly with rise in temperature. At higher temperatures, it directly combines with some metals to form predominantly ionic nitrides and with non-metals, covalent nitrides. A few typical reactions are:

$$ \begin{aligned} & 6 \mathrm{Li}+\mathrm{N_2} \xrightarrow{\text { Heat }} 2 \mathrm{Li_3} \mathrm{~N} \ & 3 \mathrm{Mg}+\mathrm{N_2} \xrightarrow{\text { Heat }} \mathrm{Mg_3} \mathrm{~N_2} \end{aligned} $$

It combines with hydrogen at about $773 \mathrm{~K}$ in the presence of a catalyst (Haber’s Process) to form ammonia:

$$ \mathrm{N_2}(\mathrm{~g})+3 \mathrm{H_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \quad 773 \mathrm{k} \quad 2 \mathrm{NH_3}(\mathrm{~g}) ; \quad \Delta_{f} \mathrm{H}^{\ominus}=-46.1 \mathrm{kJmol}^{-1} $$

Dinitrogen combines with dioxygen only at very high temperature (at about $2000 \mathrm{~K}$ ) to form nitric oxide, NO.

$$ \mathrm{N_2}+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \quad \text { Heat } \quad 2 \mathrm{NO}(\mathrm{g}) $$

Uses: The main use of dinitrogen is in the manufacture of ammonia and other industrial chemicals containing nitrogen, (e.g., calcium cyanamide). It also finds use where an inert atmosphere is required (e.g., in iron and steel industry, inert diluent for reactive chemicals). Liquid dinitrogen is used as a refrigerant to preserve biological materials, food items and in cryosurgery.

7.3 Ammonia

Preparation Ammonia is present in small quantities in air and soil where it is formed by the decay of nitrogenous organic matter e.g., urea.

$$ \mathrm{NH_2} \mathrm{CONH_2}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow\left(\mathrm{NH_4}\right)_{2} \mathrm{CO_3} \rightleftharpoons 2 \mathrm{NH_3}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+\mathrm{CO_2} $$

On a small scale ammonia is obtained from ammonium salts which decompose when treated with caustic soda or calcium hydroxide.

$$ \begin{aligned} & 2 \mathrm{NH_4} \mathrm{Cl}+\mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_2 \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{NH_3}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+\mathrm{CaCl_2} \\ & \left(\mathrm{NH_4}\right)_2 \mathrm{SO_4}+2 \mathrm{NaOH} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{NH_3}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+\mathrm{Na_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \end{aligned} $$

On a large scale, ammonia is manufactured by Haber’s process.

$$ \mathrm{N_2}(\mathrm{~g})+3 \mathrm{H_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \rightleftharpoons 2 \mathrm{NH_3}(\mathrm{~g}) ; \quad \quad \Delta_{f} H^{\ominus}=-46.1 \mathrm{~kJ} \mathrm{~mol}^{-1} $$

In accordance with Le Chatelier’s principle, high pressure would favour the formation of ammonia. The optimum conditions for the production of ammonia are a pressure of $200 \times 10^{5} \mathrm{~Pa}$ (about 200 atm), a temperature of $\sim 700 \mathrm{~K}$ and the use of a catalyst such as iron oxide with small amounts of $\mathrm{K_2} \mathrm{O}$ and $\mathrm{Al_2} \mathrm{O_3}$ to increase the rate of attainment of equilibrium. The flow chart for the production of ammonia is shown in Fig. 7.1. Earlier, iron was used as a catalyst with molybdenum as a promoter.

Properties

Ammonia is a colourless gas with a pungent odour. Its freezing and boiling points are 198.4 and $239.7 \mathrm{~K}$ respectively. In the solid and liquid states, it is associated through hydrogen bonds as in the case of water and that accounts for its higher melting and boiling points than expected on the basis of its molecular mass. The ammonia molecule is trigonal pyramidal with the nitrogen atom at the apex. It has three bond pairs and one lone pair of electrons as shown in the structure.

Ammonia gas is highly soluble in water. Its aqueous solution is weakly basic due to the formation of $\mathrm{OH}^{-}$ions.

$$ \mathrm{NH_3}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \rightleftharpoons \mathrm{NH_4}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{OH}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) $$

It forms ammonium salts with acids, e.g., $\mathrm{NH_4} \mathrm{Cl},\left(\mathrm{NH_4}\right)_{2} \mathrm{SO_4}$, etc. As a weak base, it precipitates the hydroxides (hydrated oxides in case of some metals) of many metals from their salt solutions. For example,

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{ZnSO_4}(\mathrm{aq})+2 \mathrm{NH_4} \mathrm{OH}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \mathrm{Zn} \mathrm{OH}_2(\mathrm{~s})+\left(\mathrm{NH_4}\right)_2 \mathrm{SO_4}(\mathrm{aq}) \\ & \text { (white ppt) } \\ & \mathrm{FeCl_3} \text { aq } \quad \mathrm{NH_4} \mathrm{OH} \text { aq } \quad \mathrm{Fe_2} \mathrm{O_3} \cdot x \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \quad \mathrm{NH_4} \mathrm{Cl} \text { aq } \\ & \text { brown ppt } \end{aligned} $$

The presence of a lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom of the ammonia molecule makes it a Lewis base. It donates the electron pair and forms linkage with metal ions and the formation of such complex compounds finds applications in detection of metal ions such as $\mathrm{Cu}^{2+}, \mathrm{Ag}^{+}$:

$$ \underset{\text { (blue) }}{\mathrm{Cu}^{2+}(\mathrm{aq})+4 \mathrm{NH_3}(\mathrm{aq})} \rightleftharpoons \underset{\text { (deep blue) }}{\left[\mathrm{Cu}\left(\mathrm{NH_3}\right)_{4}\right]^{2+}(\mathrm{aq})} $$

$$ \underset{\text { (colourless) }}{\mathrm{Ag}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})}+\mathrm{Cl}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow \underset{{(\text white ppt) }}{\operatorname{AgCl}(\mathrm{s})} $$

$$ \operatorname{AgCl}(\mathrm{s})+2 \mathrm{NH_3}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow\left[\mathrm{Ag}\left(\mathrm{NH_3}\right)_{2}\right] \mathrm{Cl}(\mathrm{aq}) $$

Uses: Ammonia is used to produce various nitrogenous fertilisers (ammonium nitrate, urea, ammonium phosphate and ammonium sulphate) and in the manufacture of some inorganic nitrogen compounds, the most important one being nitric acid. Liquid ammonia is also used as a refrigerant.

7.4 Oxides of Nitrogen

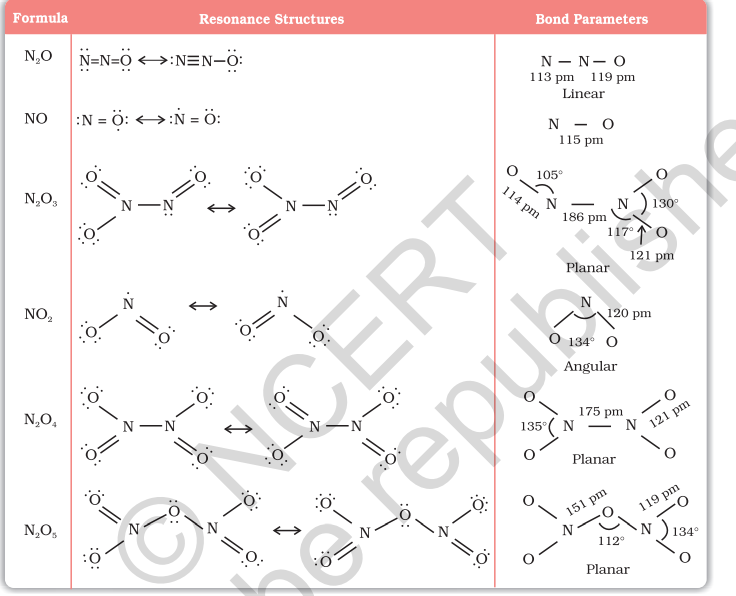

Nitrogen forms a number of oxides in different oxidation states. The names, formulas, preparation and physical appearance of these oxides are given in Table 7.3.

7.5 Nitric Acid

Nitrogen forms oxoacids such as $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~N_2} \mathrm{O_2}$ (hyponitrous acid), $\mathrm{HNO_2}$ (nitrous acid) and $\mathrm{HNO_3}$ (nitric acid). Amongst them $\mathrm{HNO_3}$ is the most important.

Preparation In the laboratory, nitric acid is prepared by heating $\mathrm{KNO_3}$ or $\mathrm{NaNO_3}$ and concentrated $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$ in a glass retort.

$$ \mathrm{NaNO_3}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \rightarrow \mathrm{NaHSO_4}+\mathrm{HNO_3} $$

On a large scale it is prepared mainly by Ostwald’s process.

This method is based upon catalytic oxidation of $\mathrm{NH_3}$ by atmospheric oxygen.

$$ 4 \mathrm{NH_3}(\mathrm{~g})+\underset{\text { (from air) }}{5 \mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g})} \frac{\mathrm{Pt} / \mathrm{Rh} \text { gauge catalyst }}{500 \mathrm{~K}, 9 \text { bar }} 4 \mathrm{NO}(\mathrm{g})+6 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{g}) $$

Nitric oxide thus formed combines with oxygen giving $\mathrm{NO_2}$.

$$ 2 \mathrm{NO}(\mathrm{g})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \rightleftharpoons 2 \mathrm{NO_2}(\mathrm{~g}) $$

Nitrogen dioxide so formed, dissolves in water to give $\mathrm{HNO_3}$.

$$ 3 \mathrm{NO_2}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{HNO_3}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{NO}(\mathrm{g}) $$

NO thus formed is recycled and the aqueous $\mathrm{HNO_3}$ can be concentrated by distillation upto $\sim 68 %$ by mass. Further concentration to $98 %$ can be achieved by dehydration with concentrated $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$.

Properties

It is a colourless liquid (f.p. $231.4 \mathrm{~K}$ and b.p. $355.6 \mathrm{~K}$ ). Laboratory grade nitric acid contains $\sim 68 %$ of the $\mathrm{HNO_3}$ by mass and has a specific gravity of 1.504 .

In the gaseous state, $\mathrm{HNO_3}$ exists as a planar molecule with the structure as shown.

In aqueous solution, nitric acid behaves as a strong acid giving hydronium and nitrate ions.

$$ \mathrm{HNO_3}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{O}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{NO_3}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) $$

Concentrated nitric acid is a strong oxidising agent and attacks most metals except noble metals such as gold and platinum. The products of oxidation depend upon the concentration of the acid, temperature and the nature of the material undergoing oxidation.

$$ \begin{aligned} & 3 \mathrm{Cu}+8 \mathrm{HNO_3} \text { (dilute) } \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{Cu}\left(\mathrm{NO_3}\right)_{2}+2 \mathrm{NO}+4 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} \\ & \mathrm{Cu}+4 \mathrm{HNO_3} \text { (conc.) } \rightarrow \mathrm{Cu}\left(\mathrm{NO}_3\right)_2+2 \mathrm{NO_2}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \end{aligned} $$

Zinc reacts with dilute nitric acid to give $\mathrm{N_2} \mathrm{O}$ and with concentrated acid to give $\mathrm{NO_2}$.

$$ \begin{aligned} & 4 \mathrm{Zn}+10 \mathrm{HNO_3} \text { (dilute) } \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{Zn}\left(\mathrm{NO_3}\right)_2+5 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+\mathrm{N_2} \mathrm{O} \ & \mathrm{Zn}+4 \mathrm{HNO_3} \text { (conc.) } \rightarrow \mathrm{Zn}\left(\mathrm{NO_3}\right)_2+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+2 \mathrm{NO_2} \end{aligned} $$

Some metals (e.g., Cr, Al) do not dissolve in concentrated nitric acid because of the formation of a passive film of oxide on the surface.

Concentrated nitric acid also oxidises non-metals and their compounds. Iodine is oxidised to iodic acid, carbon to carbon dioxide, sulphur to $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$, and phosphorus to phosphoric acid.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{I}_2 + 10 \mathrm{HNO_3} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{HIO}_3+10 \mathrm{NO}_2 + 4 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} \\ & \mathrm{C}+4 \mathrm{HNO_3} \rightarrow \mathrm{CO_2}+2 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O}+4 \mathrm{NO}_2 \\ & \mathrm{~S}_8+48 \mathrm{HNO}_3 \rightarrow 8 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{SO}_4+48 \mathrm{NO}_2+16 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} \\ & \mathrm{P}_4+20 \mathrm{HNO}_3 \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{H}_3 \mathrm{PO}_4+20 \mathrm{NO}_2+4 \mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} \end{aligned} $$

Brown Ring Test: The familiar brown ring test for nitrates depends on the ability of $\mathrm{Fe}^{2+}$ to reduce nitrates to nitric oxide, which reacts with $\mathrm{Fe}^{2+}$ to form a brown coloured complex. The test is usually carried out by adding dilute ferrous sulphate solution to an aqueous solution containing nitrate ion, and then carefully adding concentrated sulphuric acid along the sides of the test tube. A brown ring at the interface between the solution and sulphuric acid layers indicates the presence of nitrate ion in solution.

$$ \begin{gathered} \mathrm{NO_3}^-+3 \mathrm{Fe}^{2+}+4 \mathrm{H}^+ \rightarrow \mathrm{NO}+3 \mathrm{Fe}^{3+}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \\ {\left[\mathrm{Fe}\left(\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}\right)_6\right]^{2+}+\mathrm{NO} \rightarrow \underset{\text { (brown) }}{\left[\mathrm{Fe}\left(\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}\right)_5(\mathrm{NO})\right]^{2+}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}}} \end{gathered} $$

Uses: The major use of nitric acid is in the manufacture of ammonium nitrate for fertilisers and other nitrates for use in explosives and pyrotechnics. It is also used for the preparation of nitroglycerin, trinitrotoluene and other organic nitro compounds. Other major uses are in the pickling of stainless steel, etching of metals and as an oxidiser in rocket fuels.

7.6 Phosphorus — Allotropic Forms

Phosphorus is found in many allotropic forms, the important ones being white, red and black.

White phosphorus is a translucent white waxy solid. It is poisonous, insoluble in water but soluble in carbon disulphide and glows in dark (chemiluminescence). It dissolves in boiling NaOH solution in an inert atmosphere giving PH3.White phosphorus is a translucent white waxy solid. It is poisonous, insoluble in water but soluble in carbon disulphide and glows in dark (chemiluminescence). It dissolves in boiling $\mathrm{NaOH}$ solution in an inert atmosphere giving $\mathrm{PH_3}$.

$$ \mathrm{P_4}+3 \mathrm{NaOH}+3 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{PH_3}+3 \mathrm{NaH_2} \mathrm{PO_2} $$

White phosphorus is less stable and therefore, more reactive than the other solid phases under normal conditions because of angular strain in the $\mathrm{P_4}$ molecule where the angles are only $60^{\circ}$. It readily catches fire in air to give dense white fumes of $\mathrm{P_4} \mathrm{O_10}$.

$$ \mathrm{P_4}+5 \mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{P_4} \mathrm{O_10} $$

It consists of discrete tetrahedral $\mathrm{P_4}$ molecule as shown in Fig. 7.2.

Red phosphorus is obtained by heating white phosphorus at $573 \mathrm{~K}$ in an inert atmosphere for several days. When red phosphorus is heated under high pressure, a series of phases of black phosphorus is formed. Red phosphorus possesses iron grey lustre. It is odourless, nonpoisonous and insoluble in water as well as in carbon disulphide. Chemically, red phosphorus is much less reactive than white phosphorus. It does not glow in the dark.

It is polymeric, consisting of chains of $\mathrm{P_4}$ tetrahedra linked together in the manner as shown in Fig. 7.3.

Black phosphorus has two forms $\alpha$-black phosphorus and $\beta$-black phosphorus. $\alpha$-Black phosphorus is formed when red phosphorus is heated in a sealed tube at $803 \mathrm{~K}$. It can be sublimed in air and has opaque monoclinic or rhombohedral crystals. It does not oxidise in air. $\beta$-Black phosphorus is prepared by heating white phosphorus at $473 \mathrm{~K}$ under high pressure. It does not burn in air upto $673 \mathrm{~K}$.

7.7 Phosphine

Preparation Phosphine is prepared by the reaction of calcium phosphide with water or dilute HCl.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{Ca_3} \mathrm{P_2}+6 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}+2 \mathrm{PH_3} \\ & \mathrm{Ca_3} \mathrm{P_2}+6 \mathrm{HCl} \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{CaCl_2}+2 \mathrm{PH_3} \end{aligned} $$

In the laboratory, it is prepared by heating white phosphorus with concentrated $\mathrm{NaOH}$ solution in an inert atmosphere of $\mathrm{CO_2}$.

$$ \begin{array}{r} \mathrm{P_4}+3 \mathrm{NaOH}+3 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{PH_3}+3 \mathrm{NaH_2} \mathrm{PO_2} \ \ \text { (sodium hypophosphite) } \end{array} $$

When pure, it is non inflammable but becomes inflammable owing to the presence of $\mathrm{P_2} \mathrm{H_4}$ or $\mathrm{P_4}$ vapours. To purify it from the impurities, it is absorbed in $\mathrm{HI}$ to form phosphonium iodide $\left(\mathrm{PH_4} \mathrm{I}\right)$ which on treating with $\mathrm{KOH}$ gives off phosphine.

Properties

It is a colourless gas with rotten fish smell and is highly poisonous. It explodes in contact with traces of oxidising agents like $\mathrm{HNO_3}, \mathrm{Cl_2}$ and $\mathrm{Br_2}$ vapours.

It is slightly soluble in water. The solution of $\mathrm{PH_3}$ in water decomposes in presence of light giving red phosphorus and $\mathrm{H_2}$. When absorbed in copper sulphate or mercuric chloride solution, the corresponding phosphides are obtained.

$$ \begin{aligned} & 3 \mathrm{CuSO_4}+2 \mathrm{PH_3} \rightarrow \mathrm{Cu_3} \mathrm{P_2}+3 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \\ & 3 \mathrm{HgCl_2}+2 \mathrm{PH_3} \rightarrow \mathrm{Hg_3} \mathrm{P_2}+6 \mathrm{HCl} \end{aligned} $$ Phosphine is weakly basic and like ammonia, gives phosphonium compounds with acids e.g.,

$$ \mathrm{PH_3}+\mathrm{HBr} \rightarrow \mathrm{PH_4} \mathrm{Br} $$

Uses: The spontaneous combustion of phosphine is technically used in Holme’s signals. Containers containing calcium carbide and calcium phosphide are pierced and thrown in the sea when the gases evolved burn and serve as a signal. It is also used in smoke screens.

7.8 Phosphorus Halides

Phosphorus forms two types of halides, $\mathrm{PX_3}(\mathrm{X}=\mathrm{F}, \mathrm{Cl}, \mathrm{Br}, \mathrm{I})$ and $\mathrm{PX_5}(\mathrm{X}=\mathrm{F}, \mathrm{Cl}, \mathrm{Br})$.

7.8.1 Phosphorus Trichloride

Preparation It is obtained by passing dry chlorine over heated white phosphorus.

$$ \mathrm{P_4}+6 \mathrm{Cl_2} \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{PCl_3} $$

It is also obtained by the action of thionyl chloride with white phosphorus.

$$ \mathrm{P_4}+8 \mathrm{SOCl_2} \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{PCl_3}+4 \mathrm{SO_2}+2 \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{Cl_2} $$

Properties It is a colourless oily liquid and hydrolyses in the presence of moisture.

$$ \mathrm{PCl_3}+3 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3}+3 \mathrm{HCl} $$

It reacts with organic compounds containing $-\mathrm{OH}$ group such as $\mathrm{CH_3} \mathrm{COOH}, \mathrm{C_2} \mathrm{H_5} \mathrm{OH}$.

$$ \begin{aligned} & 3 \mathrm{CH_3} \mathrm{COOH}+\mathrm{PCl_3} \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{CH_3} \mathrm{COCl}+\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3} \\ & 3 \mathrm{C_2} \mathrm{H_5} \mathrm{OH}+\mathrm{PCl_3} \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{C_2} \mathrm{H_5} \mathrm{Cl}+\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3} \end{aligned} $$

It has a pyramidal shape as shown, in which phosphorus is $s p^{3}$ hybridised.

7.8.2 Phosphorus Pentachloride

Preparation Phosphorus pentachloride is prepared by the reaction of white phosphorus with excess of dry chlorine.

Phosphorus pentachloride is prepared by the reaction of white phosphorus with excess of dry chlorine.

$$ \mathrm{P_4}+10 \mathrm{Cl_2} \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{PCl_5} $$

It can also be prepared by the action of $\mathrm{SO_2} \mathrm{Cl_2}$ on phosphorus.

$$ \mathrm{P_4}+10 \mathrm{SO_2} \mathrm{Cl_2} \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{PCl_5}+10 \mathrm{SO_2} $$

Properties $\mathrm{PCl_5}$ is a yellowish white powder and in moist air, it hydrolyses to $\mathrm{POCl_3}$ and finally gets converted to phosphoric acid.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{PCl_5}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{POCl_3}+2 \mathrm{HCl} \\ & \mathrm{POCl_3}+3 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_4}+3 \mathrm{HCl} \end{aligned} $$

When heated, it sublimes but decomposes on stronger heating.

$$ \mathrm{PCl_5} \xrightarrow{\text { Heat }} \mathrm{PCl_3}+\mathrm{Cl_2} $$

It reacts with organic compounds containing –OH group converting them to chloro derivatives.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{C_2} \mathrm{H_5} \mathrm{OH}+\mathrm{PCl_5} \rightarrow \mathrm{C_2} \mathrm{H_5} \mathrm{Cl}+\mathrm{POCl_3}+\mathrm{HCl} \\ & \mathrm{CH_3} \mathrm{COOH}+\mathrm{PCl_5} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH_3} \mathrm{COCl}+\mathrm{POCl_3}+\mathrm{HCl} \end{aligned} $$

Finely divided metals on heating with $\mathrm{PCl_5}$ give corresponding chlorides

$$ \begin{aligned} & 2 \mathrm{Ag}+\mathrm{PCl_5} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{AgCl}+\mathrm{PCl_3} \\ & \mathrm{Sn}+2 \mathrm{PCl_5} \rightarrow \mathrm{SnCl_4}+2 \mathrm{PCl_3} \end{aligned} $$

It is used in the synthesis of some organic compounds, e.g., $\mathrm{C_2} \mathrm{H_5} \mathrm{Cl}, \mathrm{CH_3} \mathrm{COCl}$.

In gaseous and liquid phases, it has a trigonal bipyramidal structure as shown. The three equatorial $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{Cl}$ bonds are equivalent, while the two axial bonds are longer than equatorial bonds. This is due to the fact that the axial bond pairs suffer more repulsion as compared to equatorial bond pairs.

7.9 Oxoacids of Phosphorus

Phosphorus forms a number of oxoacids. The important oxoacids of phosphorus with their formulas, methods of preparation and the presence of some characteristic bonds in their structures are given in Table 7.5.

Table 7.5: Oxoacids of Phosphorus

| Name | Formula | Oxidation state of phosphorus | Characteristic bonds and their number | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypophosphorous (Phosphinic) | $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_2}$ | +1 | One P - OH Two P - H One P = O | white $\mathrm{P_4}+$ alkali |

| Orthophosphorous (Phosphonic) | $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3}$ | +3 | Two P - OH One P - H One P $=\mathrm{O}$ | $\mathrm{P_2} \mathrm{O_3}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$ |

| Pyrophosphorous | $\mathrm{H_4} \mathrm{P_2} \mathrm{O_5}$ | +3 | Two P - OH Two P - H Two P = O | $\mathrm{PCl_3}+\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3}$ |

| Hypophosphoric | $\mathrm{H_4} \mathrm{P_2} \mathrm{O_6}$ | +4 | Four P $-\mathrm{OH}$ Two P $=\mathrm{O}$ One P $-\mathrm{P}$ | red $\mathrm{P_4}+$ alkali |

| Orthophosphoric | $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_4}$ | +5 | Three P $-\mathrm{OH}$ One P $=\mathrm{O}$ | $\mathrm{P_4} \mathrm{O_1}$ |

| Pyrophosphoric | $\mathrm{H_4} \mathrm{P_2} \mathrm{O_7}$ | 1 | Four $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{OH}$ Two $\mathrm{P}=\mathrm{O}$ One $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{O}-\mathrm{P}$ | heat phosphoric acid |

| Metaphosphoric* | $\left(\mathrm{HPO_3}\right)_{\mathrm{n}}$ | Three $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{OH}$ Three $\mathrm{P}=\mathrm{O}$ Three $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{O}-\mathrm{P}$ | phosphorus acid $+\mathrm{Br_2}$, heat in a sealed tube |

The compositions of the oxoacids are interrelated in terms of loss or gain of $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$ molecule or $\mathrm{O}$-atom.

In oxoacids phosphorus is tetrahedrally surrounded by other atoms. All these acids contain at least one $\mathrm{P}=\mathrm{O}$ bond and one $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{OH}$ bond. The oxoacids in which phosphorus has lower oxidation state (less than +5 ) contain, in addition to $\mathrm{P}=\mathrm{O}$ and $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{OH}$ bonds, either $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{P}$ (e.g., in $\mathrm{H_4} \mathrm{P_2} \mathrm{O_6}$ ) or P-H (e.g., in $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_2}$ ) bonds but not both. These acids in +3 oxidation state of phosphorus tend to disproportionate to higher and lower oxidation states. For example, orthophophorous acid (or phosphorous acid) on heating disproportionates to give orthophosphoric acid (or phosphoric acid) and phosphine.

$$ 4 \mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3} \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_4}+\mathrm{PH_3} $$

The acids which contain $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{H}$ bond have strong reducing properties. Thus, hypophosphorous acid is a good reducing agent as it contains two $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{H}$ bonds and reduces, for example, $\mathrm{AgNO_3}$ to metallic silver.

$$ 4 \mathrm{AgNO_3}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_2} \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{Ag}+4 \mathrm{HNO_3}+\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_4} $$

These $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{H}$ bonds are not ionisable to give $\mathrm{H}^{+}$ and do not play any role in basicity. Only those $\mathrm{H}$ atoms which are attached with oxygen in $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{OH}$ form are ionisable and cause the basicity. Thus, $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3}$ and $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_4}$ are dibasic and tribasic, respectively as the structure of $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_3}$ has two $\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{OH}$ bonds and $\mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{PO_4}$ three.

7.10 Group 16 Elements

Oxygen, sulphur, selenium, tellurium, polonium and livermorium constitute Group 16 of the periodic table. This is sometimes known as group of chalcogens. The name is derived from the Greek word for brass and points to the association of sulphur and its congeners with copper. Most copper minerals contain either oxygen or sulphur and frequently the other members of the group.

7.10.1 Occurrence

Oxygen is the most abundant of all the elements on earth. Oxygen forms about $46.6 %$ by mass of earth’s crust. Dry air contains $20.946 %$ oxygen by volume.

However, the abundance of sulphur in the earth’s crust is only 0.03-0.1%. Combined sulphur exists primarily as sulphates such as gypsum $\mathrm{CaSO_4} \cdot 2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$, epsom salt $\mathrm{MgSO_4} \cdot 7 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$, baryte $\mathrm{BaSO_4}$ and sulphides such as galena $\mathrm{PbS}$, zinc blende $\mathrm{ZnS}$, copper pyrites $\mathrm{CuFeS_2}$. Traces of sulphur occur as hydrogen sulphide in volcanoes. Organic materials such as eggs, proteins, garlic, onion, mustard, hair and wool contain sulphur.

Selenium and tellurium are also found as metal selenides and tellurides in sulphide ores. Polonium occurs in nature as a decay product of thorium and uranium minerals. Livermorium is a synthetic radioactive element. Its symbol is Lv, atomic number 116, atomic mass 292 and electronic configuration [Rn] 5f 146d107s27p4. It has been produced only in a very small amount and has very short half-life (only a small fraction of one second). This limits the study of properlies of Lv.

Here, except for livermorium, important atomic and physical properties of other elements of Group16 along with their electronic configurations are given in Table 7.6. Some of the atomic, physical and chemical properties and their trends are discussed below.

7.10.2 Electronic Configuration

The elements of Group16 have six electrons in the outermost shell and have ns2np4 general electronic configuration.

7.10.3 Atomic and Ionic Radii

Due to increase in the number of shells, atomic and ionic radii increase from top to bottom in the group. The size of oxygen atom is, however, exceptionally small.

7.10.4 Ionisation Enthalpy

Ionisation enthalpy decreases down the group. It is due to increase in size. However, the elements of this group have lower ionisation enthalpy values compared to those of Group15 in the corresponding periods. This is due to the fact that Group 15 elements have extra stable halffilled p orbitals electronic configurations.

7.10.5 Electron Gain Enthalpy

Because of the compact nature of oxygen atom, it has less negative electron gain enthalpy than sulphur. However, from sulphur onwards the value again becomes less negative upto polonium.

7.10.6 Electronegativity

Next to fluorine, oxygen has the highest electronegativity value amongst the elements. Within the group, electronegativity decreases with an increase in atomic number. This implies that the metallic character increases from oxygen to polonium.

7.10.7 Physical Properties

Some of the physical properties of Group 16 elements are given in Table 7.6. Oxygen and sulphur are non-metals, selenium and tellurium metalloids, whereas polonium is a metal. Polonium is radioactive and is short lived (Half-life 13.8 days). All these elements exhibit allotropy. The melting and boiling points increase with an increase in atomic number down the group. The large difference between the melting and boiling points of oxygen and sulphur may be explained on the basis of their atomicity; oxygen exists as diatomic molecule (O2) whereas sulphur exists as polyatomic molecule (S8).

7.10.8 Chemical Properties

Oxidation states and trends in chemical reactivity

The elements of Group 16 exhibit a number of oxidation states (Table 7.6). The stability of -2 oxidation state decreases down the group. Polonium hardly shows –2 oxidation state. Since electronegativity of oxygen is very high, it shows only negative oxidation state as –2 except

Table 7.6: Some Physical Properties of Group 16 Elements

| Property | 0 | $\mathbf{S}$ | Se | Te | Po |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 8 | 16 | 34 | 52 | 84 |

| Atomic mass $/ \mathrm{g} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 16.00 | 32.06 | 78.96 | 127.60 | 210.00 |

| Electronic configuration | $[\mathrm{He}] 2 s^{2} 2 p^{4}$ | $[\mathrm{Ne}] 3 s^{2} 3 p^{4}$ | $[\mathrm{Ar}] 3 d^{10} 4 s^{2} 4 p^{4}$ | $[\mathrm{Kr}] 4 d^{10} 5 s^{2} 5 p^{4}$ | $[\mathrm{Xe}] 4 f^{4} 5 d^{10} 6 s^{2} 6 p^{4}$ |

| Covalent radius $/(\mathrm{pm})^{\mathrm{a}}$ | 66 | 104 | 117 | 137 | 146 |

| Ionic radius, $\mathrm{E}^{2-} / \mathrm{pm}$ | 140 | 184 | 198 | 221 | $230^{\mathrm{b}}$ |

| Electron gain enthalpy, $/ \Delta_{e g} H \mathrm{~kJ} \mathrm{~mol}{ }^{-1}$ | -141 | -200 | -195 | -190 | -174 |

| Ionisation enthalpy $\left(\Delta_{i} H_{1}\right)$ $/ \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 1314 | 1000 | 941 | 869 | 813 |

| Electronegativity | 3.50 | 2.58 | 2.55 | 2.01 | 1.76 |

| Density /g cm ${ }^{-3}$ (298 K) | $1.32^{\mathrm{c}}$ | $2.06^{\mathrm{d}}$ | $4.19^{\mathrm{e}}$ | 6.25 | $-\infty$ |

| Melting point/K | 55 | $393^{\mathrm{f}}$ | 490 | 725 | 520 |

| Boiling point/K | 90 | 718 | 958 | 1260 | 1235 |

| Oxidation states* | $-2,-1,1,2$ | $-2,2,4,6$ | $-2,2,4,6$ | $-2,2,4,6$ | 2,4 |

${ }^{a}$ Single bond; ${ }^{b}$ Approximate value; ${ }^{c}$ At the melting point; ${ }^{d}$ Rhombic sulphur; ${ }^{e}$ Hexagonal grey; ${ }^{f}$ Monoclinic form, $673 \mathrm{~K}$.

- Oxygen shows oxidation states of +2 and +1 in oxygen fluorides $\mathrm{OF_2}$ and $\mathrm{O_2} \mathrm{~F_2}$ respectively

in the case of $\mathrm{OF_2}$ where its oxidation state is +2 . Other elements of the group exhibit $+2,+4,+6$ oxidation states but +4 and +6 are more common. Sulphur, selenium and tellurium usually show +4 oxidation state in their compounds with oxygen and +6 with fluorine. The stability of +6 oxidation state decreases down the group and stability of +4 oxidation state increases (inert pair effect). Bonding in +4 and +6 oxidation states is primarily covalent.

Anomalous behaviour of oxygen

The anomalous behaviour of oxygen, like other members of $p$-block present in second period is due to its small size and high electronegativity. One typical example of effects of small size and high electronegativity is the presence of strong hydrogen bonding in $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$ which is not found in $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S}$.

The absence of $d$ orbitals in oxygen limits its covalency to four and in practice, rarely exceeds two. On the other hand, in case of other elements of the group, the valence shells can be expanded and covalence exceeds four.

(i) Reactivity with hydrogen: All the elements of Group 16 form hydrides of the type $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{E}(\mathrm{E}=\mathrm{O}, \mathrm{S}, \mathrm{Se}, \mathrm{Te}, \mathrm{Po})$. Some properties of hydrides are given in Table 7.7. Their acidic character increases from $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$ to $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{Te}$. The increase in acidic character can be explained in terms of decrease in bond enthalpy for the dissociation of $\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{E}$ bond down the group. Owing to the decrease in enthalpy for the dissociation of $\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{E}$ bond down the group, the thermal stability of hydrides also decreases from $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$ to $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{Po}$. All the hydrides except water possess reducing property and this character increases from $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S}$ to $\mathrm{H_2}$ Te.

Table 7.7: Properties of Hydrides of Group 16 Elements

| Property | $\mathbf{H_2} \mathrm{O}$ | $\mathbf{H_2} \mathrm{~S}$ | $\mathrm{H_2}$ Se | $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{Te}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\mathrm{m} \cdot \mathrm{p} / \mathrm{K}$ | 273 | 188 | 208 | 222 |

| b.p/K | 373 | 213 | 232 | 269 |

| $\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{E}$ distance $/ \mathrm{pm}$ | 96 | 134 | 146 | 169 |

| $\mathrm{HEH}$ angle ( $ $ | 104 | 92 | 91 | 90 |

| $\Delta_{f} \mathrm{H} / \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | -286 | -20 | 73 | 100 |

| $\Delta_{\text {diss }} \mathrm{H}(\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{E}) / \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 463 | 347 | 276 | 238 |

| Dissociation constant | $1.8 \times 10^{-16}$ | $1.3 \times 10^{-7}$ | $1.3 \times 10^{-4}$ | $2.3 \times 10^{-3}$ |

${ }^{a}$ Aqueous solution, $298 \mathrm{~K}$

(ii) Reactivity with oxygen: All these elements form oxides of the $\mathrm{EO_2}$ and $\mathrm{EO_3}$ types where $\mathrm{E}=\mathrm{S}$, Se, Te or Po. Ozone $\left(\mathrm{O_3}\right)$ and sulphur dioxide $\left(\mathrm{SO_2}\right)$ are gases while selenium dioxide $\left(\mathrm{SeO_2}\right)$ is solid. Reducing property of dioxide decreases from $\mathrm{SO_2}$ to $\mathrm{TeO_2} ; \mathrm{SO_2}$ is reducing while $\mathrm{TeO_2}$ is an oxidising agent. Besides $\mathrm{EO_2}$ type, sulphur, selenium and tellurium also form $\mathrm{EO_3}$ type oxides $\left(\mathrm{SO_3}\right).$, $\mathrm{SeO_3}, \mathrm{TeO_3}$ . Both types of oxides are acidic in nature.

(iii) Reactivity towards the halogens: Elements of Group 16 form a large number of halides of the type, $\mathrm{EX_6}, \mathrm{EX_4}$ and $\mathrm{EX_2}$ where $\mathrm{E}$ is an element of the group and $\mathrm{X}$ is a halogen. The stability of the halides decreases in the order $\mathrm{F}^{-}>\mathrm{Cl}^{-}>\mathrm{Br}^{-}>\mathrm{I}^{-}$. Amongst hexahalides, hexafluorides are the only stable halides. All hexafluorides are gaseous in nature. They have octahedral structure. Sulphur hexafluoride, $\mathrm{SF_6}$ is exceptionally stable for steric reasons.

Amongst tetrafluorides, $\mathrm{SF_4}$ is a gas, $\mathrm{SeF_4}$ a liquid and $\mathrm{TeF_4}$ a solid. These fluorides have $s p^{3} d$ hybridisation and thus, have trigonal bipyramidal structures in which one of the equatorial positions is occupied by a lone pair of electrons. This geometry is also regarded as see-saw geometry.

All elements except oxygen form dichlorides and dibromides. These dihalides are formed by $s p^{3}$ hybridisation and thus, have tetrahedral structure. The well known monohalides are dimeric in nature. Examples are $\mathrm{S_2} \mathrm{~F_2}, \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{Cl_2}, \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{Br_2}, \mathrm{Se_2} \mathrm{Cl_2}$ and $\mathrm{Se_2} \mathrm{Br_2}$. These dimeric halides undergo disproportionation as given below: :

$$ 2 \mathrm{Se_2} \mathrm{Cl_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{SeCl_4}+3 \mathrm{Se} $$

7.11 Dioxygen

Preparation Dioxygen can be obtained in the laboratory by the following ways:

(i) By heating oxygen containing salts such as chlorates, nitrates and permanganates.

$$ 2 \mathrm{KClO_3} \xrightarrow[\mathrm{MnO_2}]{\text { Heat }} 2 \mathrm{KCl}+3 \mathrm{O_2} $$

(ii) By the thermal decomposition of the oxides of metals low in the electrochemical series and higher oxides of some metals.

$$ \begin{array}{ll} 2 \mathrm{Ag_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{s}) \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{Ag}(\mathrm{s})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) ; & 2 \mathrm{~Pb_3} \mathrm{O_4}(\mathrm{~s}) \rightarrow 6 \mathrm{PbO}(\mathrm{s})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \\ \\ 2 \mathrm{HgO}(\mathrm{s}) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{Hg}(\mathrm{l})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) ; & 2 \mathrm{PbO_2}(\mathrm{~s}) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{PbO}(\mathrm{s})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \end{array} $$

(iii) Hydrogen peroxide is readily decomposed into water and dioxygen by catalysts such as finely divided metals and manganese dioxide.

$$ 2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{aq}) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(1)+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) $$

On large scale it can be prepared from water or air. Electrolysis of water leads to the release of hydrogen at the cathode and oxygen at the anode.

Industrially, dioxygen is obtained from air by first removing carbon dioxide and water vapour and then, the remaining gases are liquefied and fractionally distilled to give dinitrogen and dioxygen.

Properties

Dioxygen is a colourless and odourless gas. Its solubility in water is to the extent of $3.08 \mathrm{~cm}^{3}$ in $100 \mathrm{~cm}^{3}$ water at $293 \mathrm{~K}$ which is just sufficient for the vital support of marine and aquatic life. It liquefies at $90 \mathrm{~K}$ and freezes at $55 \mathrm{~K}$. Oxygen atom has three stable isotopes: ${ }^{16} \mathrm{O},{ }^{17} \mathrm{O}$ and ${ }^{18} \mathrm{O}$. Molecular oxygen, $\mathrm{O_2}$ is unique in being paramagnetic inspite of having even number of electrons (see Class XI Chemistry Book, Unit 4).

Dioxygen directly reacts with nearly all metals and non-metals except some metals ( e.g., Au, Pt) and some noble gases. Its combination with other elements is often strongly exothermic which helps in sustaining the reaction. However, to initiate the reaction, some external heating is required as bond dissociation enthalpy of oxgyen-oxygen double bond is high ( $493.4 \mathrm{~kJ} \mathrm{~mol}^{-1}$ ).

Some of the reactions of dioxygen with metals, non-metals and other compounds are given below:

$$ \begin{aligned} & 2 \mathrm{Ca}+\mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{CaO} \\ & 4 \mathrm{Al}+3 \mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{Al_2} \mathrm{O_3} \\ & \mathrm{P_4}+5 \mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{P_4} \mathrm{O_10} \\ & \mathrm{C}+\mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{CO_2} \\ & 2 \mathrm{ZnS}+3 \mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{ZnO}+2 \mathrm{SO_2} \\ & \mathrm{CH_4}+2 \mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{CO_2}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \end{aligned} $$

Some compounds are catalytically oxidised. For example,

$$ \begin{aligned} & 2 \mathrm{SO_2}+\mathrm{O_2} \xrightarrow{\mathrm{V_2} \mathrm{O_5}} 2 \mathrm{SO_3} \\ & 4 \mathrm{HCl}+\mathrm{O_2} \xrightarrow{\mathrm{CuCl_2}} 2 \mathrm{Cl_2}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \end{aligned} $$

Uses: In addition to its importance in normal respiration and combustion processes, oxygen is used in oxyacetylene welding, in the manufacture of many metals, particularly steel. Oxygen cylinders are widely used in hospitals, high altitude flying and in mountaineering. The combustion of fuels, e.g., hydrazines in liquid oxygen, provides tremendous thrust in rockets.

7.12 Simple Oxides

A binary compound of oxygen with another element is called oxide. As already stated, oxygen reacts with most of the elements of the periodic table to form oxides. In many cases one element forms two or more oxides. The oxides vary widely in their nature and properties.

Oxides can be simple (e.g., $\left. \mathrm{MgO}, \mathrm{Al_2} \mathrm{O_3}\right.$) or mixed $\left(\mathrm{Pb_3} \mathrm{O_4}, \mathrm{Fe_3} \mathrm{O_4}\right)$ . Simple oxides can be classified on the basis of their acidic, basic or amphoteric character. An oxide that combines with water to give an acid is termed acidic oxide (e.g., $\mathrm{SO_2}, \mathrm{Cl_2} \mathrm{O_7}, \mathrm{CO_2}, \mathrm{~N_2} \mathrm{O_5}$ ). For example, $\mathrm{SO_2}$ combines with water to give $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_3}$, an acid.

$$ \mathrm{SO_2}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_3} $$

As a general rule, only non-metal oxides are acidic but oxides of some metals in high oxidation state also have acidic character (e.g., $\mathrm{Mn_2} \mathrm{O_7}, \mathrm{CrO_3}, \mathrm{~V_2} \mathrm{O_5}$ ). The oxides which give a base with water are known as basic oxides (e.g., $\mathrm{Na_2} \mathrm{O}, \mathrm{CaO}, \mathrm{BaO}$ ). For example, $\mathrm{CaO}$ combines with water to give $\mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}$, a base.

$$ \mathrm{CaO}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{Ca}(\mathrm{OH})_{2} $$

In general, metallic oxides are basic.

Some metallic oxides exhibit a dual behaviour. They show characteristics of both acidic as well as basic oxides. Such oxides are known as amphoteric oxides. They react with acids as well as alkalies. For example, $\mathrm{Al_2} \mathrm{O_3}$ reacts with acids as well as alkalies.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{Al_2} \mathrm{O_3}\mathrm{~s}+6 \mathrm{HCl}\mathrm{aq}+9 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}\mathrm{l} \rightarrow 2\left[\mathrm{Al}\left(\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}\right)_{6}\right]^{3+}\mathrm{aq}+6 \mathrm{Cl}^-(\mathrm{aq}) \\ & \mathrm{Al_2} \mathrm{O_3}(\mathrm{~s})+6 \mathrm{NaOH}(\mathrm{aq})+3 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}1 \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{Na_3}\left[\mathrm{Al}(\mathrm{OH})_6 \right]\mathrm{aq} \end{aligned} $$

7.13 Ozone

Ozone is an allotropic form of oxygen. It is too reactive to remain for long in the atmosphere at sea level. At a height of about 20 kilometres, it is formed from atmospheric oxygen in the presence of sunlight. This ozone layer protects the earth’s surface from an excessive concentration of ultraviolet (UV) radiations.

Preparation When a slow dry stream of oxygen is passed through a silent electrical discharge, conversion of oxygen to ozone (10%) occurs. The product is known as ozonised oxygen.

$$ 3 \mathrm{O_2} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{O_3} \Delta \mathrm{H}^{\ominus}(298 \mathrm{~K})=+142 \mathrm{~kJ} \mathrm{~mol}^{-1} $$

Since the formation of ozone from oxygen is an endothermic process, it is necessary to use a silent electrical discharge in its preparation to prevent its decomposition.

If concentrations of ozone greater than 10 per cent are required, a battery of ozonisers can be used, and pure ozone (b.p. 101.1K) can be condensed in a vessel surrounded by liquid oxygen.

Properties Pure ozone is a pale blue gas, dark blue liquid and violet-black solid. Ozone has a characteristic smell and in small concentrations it is harmless. However, if the concentration rises above about 100 parts per million, breathing becomes uncomfortable resulting in headache and nausea.

Ozone is thermodynamically unstable with respect to oxygen since its decomposition into oxygen results in the liberation of heat ($\Delta \mathrm{H}$ is negative) and an increase in entropy ( $\Delta \mathrm{S}$ is positive). These two effects reinforce each other, resulting in large negative Gibbs energy change $(\Delta \mathrm{G})$ for its conversion into oxygen. It is not really surprising, therefore, high concentrations of ozone can be dangerously explosive.

Due to the ease with which it liberates atoms of nascent oxygen $\left(\mathrm{O_3} \rightarrow \mathrm{O_2}+\mathrm{O}\right)$, it acts as a powerful oxidising agent. For example, it oxidises lead sulphide to lead sulphate and iodide ions to iodine.

$\mathrm{PbS}(\mathrm{s})+4 \mathrm{O_3}(\mathrm{~g}) \rightarrow \mathrm{PbSO_4}(\mathrm{~s})+4 \mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g})$

$2 \mathrm{I}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})+\mathrm{O_3}(\mathrm{~g}) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{OH}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{I_2}(\mathrm{~s})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g})$

When ozone reacts with an excess of potassium iodide solution buffered with a borate buffer ( $\mathrm{pH} 9.2$ ), iodine is liberated which can be titrated against a standard solution of sodium thiosulphate. This is a quantitative method for estimating $\mathrm{O_3}$ gas.

Experiments have shown that nitrogen oxides (particularly nitrogen monoxide) combine very rapidly with ozone and there is, thus, the possibility that nitrogen oxides emitted from the exhaust systems of supersonic jet aeroplanes might be slowly depleting the concentration of the ozone layer in the upper atmosphere.

$$ \mathrm{NO}(\mathrm{g})+\mathrm{O_3}(\mathrm{~g}) \rightarrow \mathrm{NO_2}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) $$

Another threat to this ozone layer is probably posed by the use of freons which are used in aerosol sprays and as refrigerants.

The two oxygen-oxygen bond lengths in the ozone molecule are identical (128 pm) and the molecule is angular as expected with a bond angle of about 117o. It is a resonance hybrid of two main forms:

Uses: It is used as a germicide, disinfectant and for sterilising water. It is also used for bleaching oils, ivory, flour, starch, etc. It acts as an oxidising agent in the manufacture of potassium permanganate.

7.14 Sulphur — Allotropic Forms

Sulphur forms numerous allotropes of which the yellow rhombic ($\alpha$-sulphur) and monoclinic ( $\beta$-sulphur) forms are the most important. The stable form at room temperature is rhombic sulphur, which transforms to monoclinic sulphur when heated above $369 \mathrm{~K}$.

Rhombic sulphur ( $\alpha$-sulphur)

This allotrope is yellow in colour, m.p. $385.8 \mathrm{~K}$ and specific gravity 2.06. Rhombic sulphur crystals are formed on evaporating the solution of roll sulphur in $\mathrm{CS_2}$. It is insoluble in water but dissolves to some extent in benzene, alcohol and ether. It is readily soluble in $\mathrm{CS_2}$

Monoclinic sulphur ( $\beta$-sulphur)

Its m.p. is $393 \mathrm{~K}$ and specific gravity 1.98. It is soluble in $\mathrm{CS_2}$. This form of sulphur is prepared by melting rhombic sulphur in a dish and cooling, till crust is formed. Two holes are made in the crust and the remaining liquid poured out. On removing the crust, colourless needle shaped crystals of $\beta$-sulphur are formed. It is stable above $369 \mathrm{~K}$ and transforms into $\alpha$-sulphur below it. Conversely, $\alpha$-sulphur is stable below $369 \mathrm{~K}$ and transforms into $\beta$-sulphur above this. At $369 \mathrm{~K}$ both the forms are stable. This temperature is called transition temperature.

Both rhombic and monoclinic sulphur have $\mathrm{S_8}$ molecules. These $\mathrm{S_8}$ molecules are packed to give different crystal structures. The $\mathrm{S_8}$ ring in both the forms is puckered and has a crown shape. The molecular dimensions are given in Fig. 7.5(a).

Several other modifications of sulphur containing 6-20 sulphur atoms per ring have been synthesised in the last two decades. In cyclo- $\mathrm{S_6}$, the ring adopts the chair form and the molecular dimensions are as shown in Fig. 7.5 (b). At elevated temperatures ( 1000 K), $\mathrm{S_2}$ is the dominant species and is paramagnetic like $\mathrm{O_2}$.

7.15 Sulphur Dioxide

Preparation Sulphur dioxide is formed together with a little (6-8%) sulphur trioxide when sulphur is burnt in air or oxygen:

$$ \mathrm{S}(s)+\mathrm{O_2}(g) \rightarrow \mathrm{SO_2}(g) $$

In the laboratory it is readily generated by treating a sulphite with dilute sulphuric acid.

$$ \mathrm{SO_3}^{2-}(a q)+2 \mathrm{H}^{+}(a q) \rightarrow \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l})+\mathrm{SO_2}(g) $$

Industrially, it is produced as a by-product of the roasting of sulphide ores.

$$ 4 \mathrm{FeS_2}(s)+11 \mathrm{O_2}(g) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{Fe_2} \mathrm{O_3}(s)+8 \mathrm{SO_2}(g) $$

The gas after drying is liquefied under pressure and stored in steel cylinders.

Properties Sulphur dioxide is a colourless gas with pungent smell and is highly soluble in water. It liquefies at room temperature under a pressure of two atmospheres and boils at $263 \mathrm{~K}$.

Sulphur dioxide, when passed through water, forms a solution of sulphurous acid.

$$ \mathrm{SO_2}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(1) \quad \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_3}(a q) $$

It reacts readily with sodium hydroxide solution, forming sodium sulphite, which then reacts with more sulphur dioxide to form sodium hydrogen sulphite.

$$ \begin{aligned} & 2 \mathrm{NaOH}+\mathrm{SO_2} \rightarrow \mathrm{Na_2} \mathrm{SO_3}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \\ & \mathrm{Na_2} \mathrm{SO_3}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}+\mathrm{SO_2} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{NaHSO_3} \end{aligned} $$

In its reaction with water and alkalies, the behaviour of sulphur dioxide is very similar to that of carbon dioxide.

Sulphur dioxide reacts with chlorine in the presence of charcoal (which acts as a catalyst) to give sulphuryl chloride, $\mathrm{SO_2} \mathrm{Cl_2}$. It is oxidised to sulphur trioxide by oxygen in the presence of vanadium(V) oxide catalyst.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{SO_2}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{Cl_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \rightarrow \mathrm{SO_2} \mathrm{Cl_2}(\mathrm{l}) \\ & 2 \mathrm{SO_2}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \xrightarrow{\mathrm{V_2} \mathrm{O_5}} 2 \mathrm{SO_3}(\mathrm{~g}) \end{aligned} $$

When moist, sulphur dioxide behaves as a reducing agent. For example, it converts iron(III) ions to iron(II) ions and decolourises acidified potassium permanganate(VII) solution; the latter reaction is a convenient test for the gas.

$2\mathrm{Fe} + + \mathrm{SO} + 2\mathrm{H_2O}\rightarrow 2\mathrm{Fe} + \mathrm{SO} + 4\mathrm{H_5SO_2}+ 2\mathrm{MnO_4}+ 2\mathrm{H_2O} \rightarrow 5\mathrm{SO_4} + 4\mathrm{H_2Mn} $

The molecule of $\mathrm{SO_2}$ is angular. It is a resonance hybrid of the two canonical forms:

Uses: Sulphur dioxide is used (i) in refining petroleum and sugar (ii) in bleaching wool and silk and (iii) as an anti-chlor, disinfectant and preservative. Sulphuric acid, sodium hydrogen sulphite and calcium hydrogen sulphite (industrial chemicals) are manufactured from sulphur dioxide. Liquid SO2 is used as a solvent to dissolve a number of organic and inorganic chemicals.

7.16 Oxoacids of Sulphur

Sulphur forms a number of oxoacids such as $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_3}, \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{O_3}, \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{O_4}$, Sulphur $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{O_5}, \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_\mathrm{x}} \mathrm{O_6}\left(\mathrm{x}=2\right).$ to 5, $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}, \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{O_7}, \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_5}, \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{O_8}$. Some of these acids are unstable and cannot be isolated. They are known in aqueous solution or in the form of their salts. Structures of some important oxoacids are shown in Fig. 7.6.

7.17 Sulphuric Acid

Manufacture Sulphuric acid is one of the most important industrial chemicals worldwide. Sulphuric acid is manufactured by the Contact Process which involves three steps:

(i) burning of sulphur or sulphide ores in air to generate $\mathrm{SO_2}$.

(ii) conversion of $\mathrm{SO_2}$ to $\mathrm{SO_3}$ by the reaction with oxygen in the presence of a catalyst $\left(\mathrm{V_2} \mathrm{O_5}\right)$, and

(iii) absorption of $\mathrm{SO_3}$ in $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$ to give Oleum $\left(\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{O_7}\right)$.

A flow diagram for the manufacture of sulphuric acid is shown in (Fig. 7.7). The $\mathrm{SO_2}$ produced is purified by removing dust and other impurities such as arsenic compounds.

The key step in the manufacture of $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$ is the catalytic oxidation of $\mathrm{SO_2}$ with $\mathrm{O_2}$ to give $\mathrm{SO_3}$ in the presence of $\mathrm{V_2} \mathrm{O_5}$ (catalyst).

$$ 2 \mathrm{SO_2}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \xrightarrow{\mathrm{V_2} \mathrm{O_5}} 2 \mathrm{SO_3}(\mathrm{~g}) \Delta_{\mathrm{r}} H^{\ominus}=-196.6 \mathrm{kJmol}^{-1} $$

The reaction is exothermic, reversible and the forward reaction leads to a decrease in volume. Therefore, low temperature and high pressure are the favourable conditions for maximum yield. But the temperature should not be very low otherwise rate of reaction will become slow.

In practice, the plant is operated at a pressure of 2 bar and a temperature of $720 \mathrm{~K}$. The $\mathrm{SO_3}$ gas from the catalytic converter is absorbed in concentrated $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$ to produce oleum. Dilution of oleum with water gives $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$ of the desired concentration. In the industry two steps are carried out simultaneously to make the process a continuous one and also to reduce the cost.

$$ \mathrm{SO_3}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \rightarrow \underset{\text { (Oleum) }}{\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{~S_2} \mathrm{O_7}} $$

The sulphuric acid obtained by Contact process is 96-98% pure.

Properties

Sulphuric acid is a colourless, dense, oily liquid with a specific gravity of 1.84 at $298 \mathrm{~K}$. The acid freezes at $283 \mathrm{~K}$ and boils at $611 \mathrm{~K}$. It dissolves in water with the evolution of a large quantity of heat. Hence, care must be taken while preparing sulphuric acid solution from concentrated sulphuric acid. The concentrated acid must be added slowly into water with constant stirring.

The chemical reactions of sulphuric acid are as a result of the following characteristics: (a) low volatility (b) strong acidic character (c) strong affinity for water and (d) ability to act as an oxidising agent. In aqueous solution, sulphuric acid ionises in two steps.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{O}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{HSO_4}^{-}(\mathrm{aq}) ; K_{\mathrm{a_1}}=\operatorname{very} \text { large }\left(K_{\mathrm{a_1}}>10\right) \\ & \mathrm{HSO_4}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H_3} \mathrm{O}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{SO_4}^{2-}(\mathrm{aq}) ; K_{\mathrm{a_2}}=1.2 \times 10^{-2} \end{aligned} $$

The larger value of $K_{\mathrm{a_1}}\left(K_{\mathrm{a_1}}>10\right)$ means that $\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}$ is largely dissociated into $\mathrm{H}^{+}$and $\mathrm{HSO_4}^{-}$. Greater the value of dissociation constant $\left(K_{\mathrm{a}}\right)$, the stronger is the acid.

The acid forms two series of salts: normal sulphates (such as sodium sulphate and copper sulphate) and acid sulphates (e.g., sodium hydrogen sulphate).

Sulphuric acid, because of its low volatility can be used to manufacture more volatile acids from their corresponding salts.

$$ \begin{gathered} 2 \mathrm{MX}+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{HX}+\mathrm{M_2} \mathrm{SO_4}\left(\mathrm{X}=\mathrm{F}, \mathrm{Cl}, \mathrm{NO_3}\right) \\ (\mathrm{M}=\text { Metal }) \end{gathered} $$

Concentrated sulphuric acid is a strong dehydrating agent. Many wet gases can be dried by passing them through sulphuric acid, provided the gases do not react with the acid. Sulphuric acid removes water from organic compounds; it is evident by its charring action on carbohydrates.

$$ \mathrm{C_12} \mathrm{H_22} \mathrm{O_11} \xrightarrow{\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4}} 12 \mathrm{C}+11 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} $$

Hot concentrated sulphuric acid is a moderately strong oxidising agent. In this respect, it is intermediate between phosphoric and nitric acids. Both metals and non-metals are oxidised by concentrated sulphuric acid, which is reduced to $\mathrm{SO_2}$.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{Cu}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \text { (conc.) } \rightarrow \mathrm{CuSO_4}+\mathrm{SO_2}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \\ & \mathrm{S}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \text { (conc.) } \rightarrow 3 \mathrm{SO_2}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \\ & \mathrm{C}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{SO_4} \text { (conc.) } \rightarrow \mathrm{CO_2}+2 \mathrm{SO_2}+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O} \end{aligned} $$

Uses: Sulphuric acid is a very important industrial chemical. A nation’s industrial strength can be judged by the quantity of sulphuric acid it produces and consumes. It is needed for the manufacture of hundreds of other compounds and also in many industrial processes. The bulk of sulphuric acid produced is used in the manufacture of fertilisers (e.g., ammonium sulphate, superphosphate). Other uses are in: (a) petroleum refining (b) manufacture of pigments, paints and dyestuff intermediates (c) detergent industry (d) metallurgical applications e.g., cleansing metals before enameling, electroplating and galvanising (e) storage batteries (f) in the manufacture of nitrocellulose products and (g) as a laboratory reagent.

7.18 Group 17 Elements

Fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, astatine and tennessine are members of Group 17. These are collectively known as the halogens (Greek halo means salt and genes means born i.e., salt producers). The halogens are highly reactive non-metallic elements. Like Groups 1 and 2, the elements of Group 17 show great similarity amongst themselves. That much similarity is not found in the elements of other groups of the periodic table. Also, there is a regular gradation in their physical and chemical properties. Astatine and tennessine are radioactive elements.

7.18.1 Occurrence

Fluorine and chlorine are fairly abundant while bromine and iodine less so. Fluorine is present mainly as insoluble fluorides (fluorspar $\mathrm{CaF_2}$, cryolite $\mathrm{Na_3} \mathrm{AlF_6}$ and fluoroapatite $3 \mathrm{Ca_3}\left(\mathrm{PO_4}\right)_{2} \cdot \mathrm{CaF_2}$ ) and small quantities are present in soil, river water plants and bones and teeth of animals. Sea water contains chlorides, bromides and iodides of sodium, potassium, magnesium and calcium, but is mainly sodium chloride solution $(2.5 %$ by mass). The deposits of dried up seas contain these compounds, e.g., sodium chloride and carnallite, $\mathrm{KCl} . \mathrm{MgCl_2} \cdot 6 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}$. Certain forms of marine life contain iodine in their systems; various seaweeds, for example, contain upto $0.5 %$ of iodine and Chile saltpetre contains upto $0.2 %$ of sodium iodate.

The important atomic and physical properties of Group 17 elements along with their electronic configurations are given in Table 7.8.

Table 7.8: Atomic and Physical Properties of Halogens

| Property | $\mathbf{F}$ | Cl | Br | I | $\mathbf{A t}^{\mathrm{a}}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 9 | 17 | 35 | 53 | 85 |

| Atomic mass $/ \mathrm{g} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 19.00 | 35.45 | 79.90 | 126.90 | 210 |

| Electronic configuration | $[\mathrm{He}] 2 s^{2} 2 p^{5}$ | $[\mathrm{Ne}] 3 s^{2} 3 p^{5}$ | $[\mathrm{Ar}] 3 d^{10} 4 s^{2} 4 p^{5}$ | $[\mathrm{Kr}] 4 d^{10} 5 s^{2} 5 p^{5}$ | $[\mathrm{Xe}] 4 f^{44} 5 d^{10} 6 s^{2} 6 p^{5}$ |

| Covalent radius/pm | 64 | 99 | 114 | 133 | - |

| Ionic radius $\mathrm{X}^{-} / \mathrm{pm}$ | 133 | 184 | 196 | 220 | - |

| Ionisation enthalpy $/ \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 1680 | 1256 | 1142 | 1008 | - |

| Electron gain enthalpy $/ \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | -333 | -349 | -325 | -296 | - |

| Electronegativity $^{\mathrm{b}}$ | 4 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.2 |

| $\Delta_{\mathrm{Hyd}} H\left(\mathrm{X}^{-}\right) / \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 515 | 381 | 347 | 305 | - |

| $\mathbf{F_2}$ | $\mathbf{C l_2}$ | $\mathbf{B r_2}$ | $\mathbf{I_2}$ | - | |

| Melting point/K | 54.4 | 172.0 | 265.8 | 386.6 | - |

| Boiling point/K | 84.9 | 239.0 | 332.5 | 458.2 | - |

| Density $/ \mathrm{g} \mathrm{cm}^{-3}$ | $1.5(85)^{\mathrm{c}}$ | $1.66(203)^{\mathrm{c}}$ | $3.19(273)^{\mathrm{c}}$ | $4.94(293)^{\mathrm{d}}$ | - |

| Distance $\mathrm{X}-\mathrm{X} / \mathrm{pm}$ | 143 | 199 | 228 | 266 | - |

| Bond dissociation enthalpy $/\left(\mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}\right)$ | 158.8 | 242.6 | 192.8 | 151.1 | - |

| $E^{\ominus} / V^{e}$ | 2.87 | 1.36 | 1.09 | 0.54 | - |

${ }^{a}$ Radioactive; ${ }^{b}$ Pauling scale; ${ }^{c}$ For the liquid at temperatures $(\mathrm{K})$ given in the parentheses; ${ }^{d}$ solid; ${ }^{e}$ The half-cell reaction is $\mathrm{X_2}(\mathrm{~g})+2 e^{-} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{X}(\mathrm{aq})$.

The trends of some of the atomic, physical and chemical properties are discussed below.

Here important atomic and physical properties of Group 17 elements other than tennessine are given along with their electronic configurations [Table 7.8, page 198]. Tennessine is a synthetic radioactive element. Its symbol is Ts, atomic number 117, atomic mass 294 and electronic configuration [Rn] 5f 146d107s27p5. Only very small amount of the element could be prepared. Also its half life is in milliseconds only. That is why its chemistry could not be established.

7.18.2 Electronic Configuration

All these elements have seven electrons in their outermost shell (ns2np5) which is one electron short of the next noble gas.

7.18.3 Atomic and Ionic Radii

The halogens have the smallest atomic radii in their respective periods due to maximum effective nuclear charge. The atomic radius of fluorine like the other elements of second period is extremely small. Atomic and ionic radii increase from fluorine to iodine due to increasing number of quantum shells.

7.18.4 Ionisation Enthalpy

They have little tendency to lose electron. Thus they have very high ionisation enthalpy. Due to increase in atomic size, ionisation enthalpy decreases down the group.

7.18.5 Electron Gain Enthalpy

Halogens have maximum negative electron gain enthalpy in the corresponding periods. This is due to the fact that the atoms of these elements have only one electron less than stable noble gas configurations. Electron gain enthalpy of the elements of the group becomes less negative down the group. However, the negative electron gain enthalpy of fluorine is less than that of chlorine. It is due to small size of fluorine atom. As a result, there are strong interelectronic repulsions in the relatively small 2p orbitals of fluorine and thus, the incoming electron does not experience much attraction.

7.18.6 Electronegativity

They have very high electronegativity. The electronegativity decreases down the group. Fluorine is the most electronegative element in the periodic table.

7.18.7 Physical Properties

Halogens display smooth variations in their physical properties. Fluorine and chlorine are gases, bromine is a liquid and iodine is a solid. Their melting and boiling points steadily increase with atomic number. All halogens are coloured. This is due to absorption of radiations in visible region which results in the excitation of outer electrons to higher energy level. By absorbing different quanta of radiation, they display different colours. For example, $\mathrm{F_2}$, has yellow, $\mathrm{Cl_2}$, greenish yellow, $\mathrm{Br_2}$, red and $\mathrm{I_2}$, violet colour. Fluorine and chlorine react with water. Bromine and iodine are only sparingly soluble in water but are soluble in various organic solvents such as chloroform, carbon tetrachloride, carbon disulphide and hydrocarbons to give coloured solutions.

One curious anomaly we notice from Table 7.8 is the smaller enthalpy of dissociation of $\mathrm{F_2}$ compared to that of $\mathrm{Cl_2}$ whereas $\mathrm{X}-\mathrm{X}$ bond dissociation enthalpies from chlorine onwards show the expected trend: $\mathrm{Cl}-\mathrm{Cl}>\mathrm{Br}-\mathrm{Br}>\mathrm{I}-\mathrm{I}$. A reason for this anomaly is the relatively large electron-electron repulsion among the lone pairs in $\mathrm{F_2}$ molecule where they are much closer to each other than in case of $\mathrm{Cl_2}$.

7.18.8 Chemical Properties

All the halogens exhibit -1 oxidation state. However, chlorine, bromine and iodine exhibit $+1,+3,+5$ and +7 oxidation states also as explained below:

The higher oxidation states of chlorine, bromine and iodine are realised mainly when the halogens are in combination with the small and highly electronegative fluorine and oxygen atoms. e.g., in interhalogens, oxides and oxoacids. The oxidation states of +4 and +6 occur in the oxides and oxoacids of chlorine and bromine. The fluorine atom has no d orbitals in its valence shell and therefore cannot expand its octet. Being the most electronegative, it exhibits only –1 oxidation state.

All the halogens are highly reactive. They react with metals and non-metals to form halides. The reactivity of the halogens decreases down the group.

The ready acceptance of an electron is the reason for the strong oxidising nature of halogens. $\mathrm{F_2}$ is the strongest oxidising halogen and it oxidises other halide ions in solution or even in the solid phase. In general, a halogen oxidises halide ions of higher atomic number.

$$ \begin{aligned} & \mathrm{F_2}+2 \mathrm{X} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{~F}^{-}+\mathrm{X_2}(\mathrm{X}=\mathrm{Cl}, \text { Br or } \mathrm{I}) \\ & \mathrm{Cl_2}+2 \mathrm{X}^{-} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{Cl}^{-}+\mathrm{X_2}(\mathrm{X}=\mathrm{Br} \text { or } \mathrm{I}) \\ & \mathrm{Br_2}+2 \mathrm{I}^{-} \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{Br}^{-}+\mathrm{I_2} \end{aligned} $$

The decreasing oxidising ability of the halogens in aqueous solution down the group is evident from their standard electrode potentials (Table 7.8) which are dependent on the parameters indicated below:

The relative oxidising power of halogens can further be illustrated by their reactions with water. Fluorine oxidises water to oxygen whereas chlorine and bromine react with water to form corresponding hydrohalic and hypohalous acids. The reaction of iodine with water is nonspontaneous. In fact, I– can be oxidised by oxygen in acidic medium; just the reverse of the reaction observed with fluorine.

$$ \begin{aligned} & 2 \mathrm{~F_2}(\mathrm{~g})+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \rightarrow 4 \mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+4 \mathrm{~F}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \\ & \mathrm{X_2}(\mathrm{~g})+\mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(\mathrm{l}) \rightarrow \mathrm{HX}(\mathrm{aq})+\operatorname{HOX}(\mathrm{aq}) \\ & (\text { where } \mathrm{X}=\mathrm{Cl} \text { or Br }) \\ & 4 \mathrm{I}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})+4 \mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{~g}) \rightarrow 2 \mathrm{I_2}(\mathrm{~s})+2 \mathrm{H_2} \mathrm{O}(1) \end{aligned} $$

Anomalous behaviour of fluorine

Like other elements of p-block present in second period of the periodic table, fluorine is anomalous in many properties. For example, ionisation enthalpy, electronegativity, and electrode potentials are all higher for fluorine than expected from the trends set by other halogens. Also, ionic and covalent radii, m.p. and b.p., enthalpy of bond dissociation and electron gain enthalpy are quite lower than expected. The anomalous behaviour of fluorine is due to its small size, highest electronegativity, low F-F bond dissociation enthalpy, and non availability of d orbitals in valence shell.

Most of the reactions of fluorine are exothermic (due to the small and strong bond formed by it with other elements). It forms only one oxoacid while other halogens form a number of oxoacids. Hydrogen fluoride is a liquid (b.p. 293 K) due to strong hydrogen bonding. Hydrogen bond is formed in HF due to small size and high electronegativity of fluorine. Other hydrogen halides which have bigger size and less electronegativity are gases.

Most of the reactions of fluorine are exothermic (due to the small and strong bond formed by it with other elements). It forms only one oxoacid while other halogens form a number of oxoacids. Hydrogen fluoride is a liquid (b.p. $293 \mathrm{~K}$ ) due to strong hydrogen bonding. Other hydrogen halides are gases.

(i) Reactivity towards hydrogen: They all react with hydrogen to give hydrogen halides but affinity for hydrogen decreases from fluorine to iodine. Hydrogen halides dissolve in water to form hydrohalic acids. Some of the properties of hydrogen halides are given in Table 7.9. The acidic strength of these acids varies in the order: $\mathrm{HF}<\mathrm{HCl}<\mathrm{HBr}<\mathrm{HI}$. The stability of these halides decreases down the group due to decrease in bond $(\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{X})$ dissociation enthalpy in the order: $\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{F}>\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{Cl}>\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{Br}>\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{I}$.

Table 7.9: Properties of Hydrogen Halides

| Property | HF | HCl | HBr | HI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting point/K | 190 | 159 | 185 | 222 |

| Boiling point/K | 293 | 189 | 206 | 238 |

| Bond length $(\mathrm{H}-\mathrm{X}) / \mathrm{pm}$ | 91.7 | 127.4 | 141.4 | 160.9 |

| $\Delta_{\text {diss }} \mathrm{H}^{\ominus} / \mathrm{kJ} \mathrm{mol}^{-1}$ | 574 | 432 | 363 | 295 |

| $p K_{\mathrm{a}}$ | 3.2 | -7.0 | -9.5 | -10.0 |