Chapter 01 Exception Handling in Python

“I like my code to be elegant and efficient. The logic should be straightforward to make it hard for bugs to hide, the dependencies minimal to ease maintenance, error handling complete according to an articulated strategy, and performance close to optimal so as not to tempt people to make the code messy with unprincipled optimization. Clean code does one thing well.”

- Bjarne Stroustrup

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Sometimes while executing a Python program, the program does not execute at all or the program executes but generates unexpected output or behaves abnormally. These occur when there are syntax errors, runtime errors or logical errors in the code. In Python, exceptions are errors that get triggered automatically. However, exceptions can be forcefully triggered and handled through program code. In this chapter, we will learn about exception handling in Python programs.

1.2 SYNTAX ERRORS

Syntax errors are detected when we have not followed the rules of the particular programming language while writing a program. These errors are also known as parsing errors. On encountering a syntax error, the interpreter does not execute the program unless we rectify the errors, save and rerun the program. When a syntax error is encountered while working in shell mode, Python displays the name of the error and a small description about the error as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: A syntax error displayed in Python shell mode

So, a syntax error is reported by the Python interpreter giving a brief explanation about the error and a suggestion to rectify it.

Similarly, when a syntax error is encountered while running a program in script mode as shown in Figure 1.2 , a dialog box specifying the name of the error (Figure 1.3) and a small description about the error is displayed.

1.3 EXCEPTIONS

Even if a statement or expression is syntactically correct, there might arise an error during its execution. For example, trying to open a file that does not exist, division by zero and so on. Such types of errors might disrupt the normal execution of the program and are called exceptions.

An exception is a Python object that represents an error. When an error occurs during the execution of a program, an exception is said to have been raised. Such an exception needs to be handled by the programmer so that the program does not terminate abnormally. Therefore, while designing a program, a programmer may anticipate such erroneous situations that may arise during its execution and can address them by including appropriate code to handle that exception.

It is to be noted that SyntaxError shown at Figures 1.1 and 1.3 is also an exception. But, all other exceptions are generated when a program is syntactically correct.

1.4 BUILT-IN EXCEPTIONS

Commonly occurring exceptions are usually defined in the compiler/interpreter. These are called built-in exceptions.

Python’s standard library is an extensive collection of built-in exceptions that deals with the commonly occurring errors (exceptions) by providing the standardized solutions for such errors. On the occurrence of any built-in exception, the appropriate exception handler code is executed which displays the reason along with the raised exception name. The programmer then has to take appropriate action to handle it. Some of the commonly occurring built-in exceptions that can be raised in Python are explained in Table 1.1.

| S. No | Name of the Built- in Exception | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | SyntaxError | It is raised when there is an error in the syntax of the Python code. |

| 2. | ValueError | It is raised when a built-in method or operation receives an argument that has the right data type but mismatched or inappropriate values. |

| 3. | IOError | It is raised when the file specified in a program statement cannot be opened. |

| 4 | Keyboardinterrupt | It is raised when the user accidentally hits the Delete or Esc key while executing a program due to which the normal flow of the program is interrupted. |

| 5 | ImportError | It is raised when the requested module definition is not found. |

| 6 | EOFError | It is raised when the end of file condition is reached without reading any data by input(). |

| 7 | ZeroDivisionError | It is raised when the denominator in a division operation is zero. |

| 8 | IndexError | It is raised when the index or subscript in a sequence is out of range. |

| 9 | NameError | It is raised when a local or global variable name is not defined. |

| 10 | IndentationError | It is raised due to incorrect indentation in the program code. |

| 11 | TypeError | It is raised when an operator is supplied with a value of incorrect data type. |

| 12 | OverFlowError | It is raised when the result of a calculation exceeds the maximum limit for numeric data type. |

Figure 1.4 shows the built-in exceptions viz, ZeroDivisionError, NameEError, and TypeError raised by the Python interpreter in different situations.

Figure 1.4: Example of built-in exceptions

A programmer can also create custom exceptions to suit one’s requirements. These are called user-defined exceptions. We will learn how to handle exceptions in the next section.

1.5 RAISING EXCEPTIONS

Each time an error is detected in a program, the Python interpreter raises (throws) an exception. Exception handlers are designed to execute when a specific exception is raised. Programmers can also forcefully raise exceptions in a program using the raise and assert statements. Once an exception is raised, no further statement in the current block of code is executed. So, raising an exception involves interrupting the normal flow execution of program and jumping to that part of the program (exception handler code) which is written to handle such exceptional situations.

1.5.1 The raise Statement

The raise statement can be used to throw an exception. The syntax of raise statement is:

raise exception-name[(optional argument)]

The argument is generally a string that is displayed when the exception is raised. For example, when an exception is raised as shown in Figure 1.5, the message “OOPS : An Exception has occurred” is displayed along with a brief description of the error.

Figure 1.5: Use of the raise statement to throw an exception

The error detected may be a built-in exception or may be a user-defined one. Consider the example given in Figure 1.6 that uses the raise statement to raise a built-in exception called IndexError.

Note: In this case, the user has only raised the exception but has not displayed any error message explicitly.

In Figure 1.6, since the value of variable length is greater than the length of the list numbers, an IndexError exception will be raised. The statement following the raise statement will not be executed. So the message “NO EXECUTION” will not be displayed in this case.

As we can see in Figure 1.6, in addition to the error message displayed, Python also displays a stack Traceback. This is a structured block of text that contains information about the sequence of function calls that have been made in the branch of execution of code in which the exception was raised. In Figure 1.6, the error has been encountered in the most recently called function that has been executed.

Figure 1.6: Use of raise statement with built-in exception

Note: We will learn about Stack in Chapter 3.

1.5.2 The assert Statement

An assert statement in Python is used to test an expression in the program code. If the result after testing comes false, then the exception is raised. This statement is generally used in the beginning of the function or after a function call to check for valid input. The syntax for assert statement is:

assert Expression[, arguments]

On encountering an assert statement, Python evaluates the expression given immediately after the assert keyword. If this expression is false, an AssertionError exception is raised which can be handled like any other exception. Consider the code given in Program 1-1.

Program 1-1 Use of assert statement

print(“use of assert statement”)

def negativecheck(number):

print (negativecheck(100))

print (negativecheck(-350))

Figure 1.7: Output of Program 1-1.

In the code, the assert statement checks for the value of the variable number. In case the number gets a negative value, AssertionError will be thrown, and subsequent statements will not be executed. Hence, on passing a negative value (-350) as an argument, it results in AssertionError and displays the message “OOPS…. Negative Number”. The output of the code is shown in Figure 1.7.

1.6 HANDLING EXCEPTIONS

Each and every exception has to be handled by the programmer to avoid the program from crashing abruptly. This is done by writing additional code in a program to give proper messages or instructions to the user on encountering an exception. This process is known as exception handling.

1.6.1 Need for Exception Handling

Exception handling is being used not only in Python programming but in most programming languages like C++, Java, Ruby, etc. It is a useful technique that helps in capturing runtime errors and handling them so as to avoid the program getting crashed. Following are some of the important points regarding exceptions and their handling:

- Python categorises exceptions into distinct types so that specific exception handlers (code to handle that particular exception) can be created for each type.

- Exception handlers separate the main logic of the program from the error detection and correction code. The segment of code where there is any possibility of error or exception, is placed inside one block. The code to be executed in case the exception has occurred, is placed inside another block. These statements for detection and reporting the exception do not affect the main logic of the program.

- The compiler or interpreter keeps track of the exact position where the error has occurred.

- Exception handling can be done for both user-defined and built-in exceptions.

A runtime system refers to the execution of the statements given in the program. It is a complex mechanism consisting of hardware and software that comes into action as soon as the program, written in any programming language, is put for execution.

1.6.2 Process of Handling Exception

When an error occurs, Python interpreter creates an object called the exception object. This object contains information about the error like its type, file name and position in the program where the error has occurred. The object is handed over to the runtime system so that it can find an appropriate code to handle this particular exception. This process of creating an exception object and handing it over to the runtime system is called throwing an exception. It is important to note that when an exception occurs while executing a particular program statement, the control jumps to an exception handler, abandoning execution of the remaining program statements.

The runtime system searches the entire program for a block of code, called the exception handler that can handle the raised exception. It first searches for the method in which the error has occurred and the exception has been raised. If not found, then it searches the method from which this method (in which exception was raised) was called. This hierarchical search in reverse order continues till the exception handler is found. This entire list of methods is known as call stack. When a suitable handler is found in the call stack, it is executed by the runtime process. This process of executing a suitable handler is known as catching the exception. If the runtime system is not able to find an appropriate exception after searching all the methods in the call stack, then the program execution stops.

The flowchart in Figure 1.8 describes the exception handling process.

Figure 1.8: Steps of handling exception

1.6.3 Catching Exceptions

An exception is said to be caught when a code that is designed to handle a particular exception is executed. Exceptions, if any, are caught in the try block and handled in the except block. While writing or debugging a program, a user might doubt an exception to occur in a particular part of the code. Such suspicious lines of codes are put inside a try block. Every try block is followed by an except block. The appropriate code to handle each of the possible exceptions (in the code inside the try block) are written inside the except clause.

While executing the program, if an exception is encountered, further execution of the code inside the try block is stopped and the control is transferred to the except block. The syntax of try … except clause is as follows:

try:

except [exception-name]:

Consider the Program 1-2 given below:

Program 1-2 Using try..except block

print (“Practicing for try block”)

try:

except ZeroDivisionError:

print(“OUTSIDE try..except block”)

In Program 1-2, the ZeroDivisionError exception is handled. If the user enters any non-zero value as denominator, the quotient will be displayed along with the message “Division performed successfully”, as shown in Figure 1.10. The except clause will be skipped in this case. So, the next statement after the try..except block is executed and the message “OUTSIDE try.. except block” is displayed.

However, if the user enters the value of denom as zero (0), then the execution of the try block will stop. The control will shift to the except block and the message “Denominator as Zero…. not allowed” will be displayed, as shown in Figure 1.11. Thereafter, the statement following the try..except block is executed and the message “OUTSIDE try..except block” is displayed in this case also.

Figure 1.9: Output without an error

Figure 1.10: Output with exception raised

Sometimes, a single piece of code might be suspected to have more than one type of error. For handling such situations, we can have multiple except blocks for a single try block as shown in the Program 1-3.

Program 1-3 Use of multiple except clauses

print (“Handling multiple exceptions”)

try:

except ZeroDivisionError:

except ValueError:

In the code, two types of exceptions (ZeroDivisionError and ValueError) are handled using two except blocks for a single try block. When an exception is raised, a search for the matching except block is made till it is handled. If no match is found, then the program terminates.

However, if an exception is raised for which no handler is created by the programmer, then such an exception can be handled by adding an except clause without specifying any exception. This except clause should be added as the last clause of the try..except block. The Program 1-4 given below along with the output given in Figure 1.11 explains this.

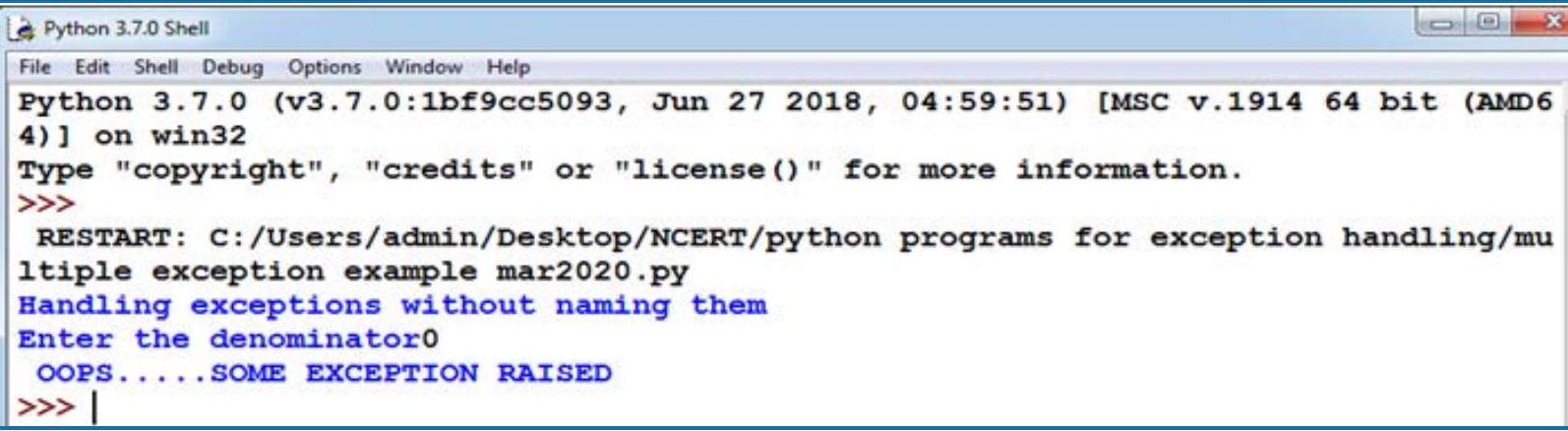

Program 1-4 Use of except without specifying an exception

print (“Handling exceptions without naming them”)

try:

except ValueError:

except:

If the above code is executed, and the denominator entered is 0 (zero), the handler for ZeroDivisionEr ror exception will be searched. Since it is not present, the last except clause (without any specified exception) will be executed, so the message " OOPS…..SOME EXCEPTION RAISED" will be displayed.

Figure 1.11: Output of Program 1-4

1.6.4 try . . . except…else clause

We can put an optional else clause along with the try… except clause. An except block will be executed only if some exception is raised in the try block. But if there is no error then none of the except blocks will be executed. In this case, the statements inside the else clause will be executed. Program 1-5 along with its output explains the use of else block with the try… except block.

Program 1-5 Use of else clause

print (“Handling exception using try…except…else”)

try:

except ZeroDivisionError:

except ValueError:

else:

Output:

Figure 1.12: Output of Program 1-5.

1.7 FINALLY CLAUSE

The try statement in Python can also have an optional finally clause. The statements inside the finally block are always executed regardless of whether an exception has occurred in the try block or not. It is a common practice to use finally clause while working with files to ensure that the file object is closed. If used, finally should always be placed at the end of try clause, after all except blocks and the else block.

Program 1-6 Use of finally clause

print (“Handling exception using try…except…else…finally”)

try:

except ZeroDivisionError:

except ValueError:

else:

finally:

In the above program, the message “OVER AND OUT” will be displayed irrespective of whether an exception is raised or not.

1.6.1 Recovering and continuing with finally clause

If an error has been detected in the try block and the exception has been thrown, the appropriate except block will be executed to handle the error. But if the exception is not handled by any of the except clauses, then it is re-raised after the execution of the finally block. For example, Program 1.4 contains only the except block for ZeroDivisionError. If any other type of error occurs for which there is no handler code (except clause) defined, then also the finally clause will be executed first. Consider the code given in Program 1-7 to understand these concepts.

Program 1-7 Recovering through finally clause

print (” Practicing for try block”)

try:

except ZeroDivisionError:

else:

finally:

While executing the above code, if we enter a non-numeric data as input, the finally block will be executed. So, the message “OVER AND OUT” will be displayed. Thereafter the exception for which handler is not present will be re-raised. The output of Program 1-7 is shown in Figure 1.13.

Figure 1.13: Output of Program 1-7

After execution of finally block, Python transfers the control to a previously entered try or to the next higher level default exception handler. In such a case, the statements following the finally block is executed. That is, unlike except, execution of the finally clause does not terminate the exception. Rather, the exception continues to be raised after execution of finally.

To summarise, we put a piece of code where there are possibilities of errors or exceptions to occur inside a try block. Inside each except clause we define handler codes to handle the matching exception raised in the try block. The optional else clause contains codes to be executed if no exception occurs. The optional finally block contains codes to be executed irrespective of whether an exception occurs or not.

SUMMARY

- Syntax errors or parsing errors are detected when we have not followed the rules of the particular programming language while writing a program.

- When syntax error is encountered, Python displays the name of the error and a small description about the error.

- The execution of the program will start only after the syntax error is rectified.

- An exception is a Python object that represents an error.

- Syntax errors are also handled as exceptions.

- The exception needs to be handled by the programmer so that the program does not terminate abruptly.

- When an exception occurs during execution of a program and there is a built-in exception defined for that, the error message written in that exception is displayed. The programmer then has to take appropriate action and handle it.

- Some of the commonly occurring built-in exceptions are SyntaxError, ValueError, IOError, KeyboardInterrupt, ImportError, EOFError, ZeroDivisionError, IndexError, NameError, IndentationError, TypeError, and overflowerror.

- When an error is encountered in a program, Python interpreter raises or throws an exception.

- Exception Handlers are the codes that are designed to execute when a specific exception is raised.

- Raising an exception involves interrupting the normal flow of the program execution and jumping to the exception handler.

- Raise and assert statements are used to raise exceptions.

- The process of exception handling involves writing additional code to give proper messages or instructions to the user. This prevents the program from crashing abruptly. The additional code is known as an exception handler.

- An exception is said to be caught when a code that is designed to handle a particular exception is executed.

- An exception is caught in the try block and handles in except block.

- The statements inside the finally block are always executed regardless of whether an exception occurred in the try block or not.

EXERCISE

1. “Every syntax error is an exception but every exception cannot be a syntax error.” Justify the statement.

2. When are the following built-in exceptions raised? Give examples to support your answers.

a) ImportError

b) IOError

c) NameError

d) ZeroDivisionError

3. What is the use of a raise statement? Write a code to accept two numbers and display the quotient. Appropriate exception should be raised if the user enters the second number (denominator) as zero (0).

4. Use assert statement in Question No. 3 to test the division expression in the program.

5. Define the following:

a) Exception Handling

b) Throwing an exception

c) Catching an exception

6. Explain catching exceptions using try and except block.

7. Consider the code given below and fill in the blanks.

print (” Learning Exceptions…”)

try:

except _____________:

except ____________:

else:

___________:

8. You have learnt how to use math module in Class XI. Write a code where you use the wrong number of arguments for a method (say sqrt() or pow()). Use the exception handling process to catch the ValueError exception.

9. What is the use of finally clause? Use finally clause in the problem given in Question No. 7.