Chapter 08 Eighteenth-Century Political Formations

If you look at Maps 1 and 2 closely, you will see Lomething significant happening in the subcontinent during the first half of the eighteenth century. Notice how the boundaries of the Mughal Empire were reshaped by the emergence of a number of independent

Map 1 State formations in the eighteenth century.

kingdoms. By 1765, notice how another power, the British, had successfully grabbed major chunks of territory in eastern India. What these maps tell us is that political conditions in eighteenth-century India changed quite dramatically and within a relatively short span of time.

In this chapter, we will read about the emergence of new political groups in the subcontinent during the first half of the eighteenth century roughly from 1707, when Aurangzeb died, till the third battle of Panipat in 1761.

Map 2 British territories in the mid-eighteenth century.

The Crisis of the Empire and the Later Mughals

In Chapter 4, you saw how the Mughal Empire reached the height of its success and started facing a variety of crises towards the closing years of the seventeenth century. These were caused by a number of factors. Emperor Aurangzeb had depleted the military and financial resources of his empire by fighting a long war in the Deccan.

See Chapter 4, Table 1. Which group of people challenged Mughal authority for the longest time in Aurangzeb’s reign?

Under his successors, the efficiency of the imperial administration broke down. It became increasingly difficult for the later Mughal emperors to keep a check on their powerful mansabdars. Nobles appointed as governors (subadars) often controlled the offices of revenue and military administration (diwani and faujdari) as well. This gave them extraordinary political, economic and military powers over vast regions of the Mughal Empire. As the governors consolidated their control over the provinces, the periodic remission of revenue to the capital declined.

Peasant and zamindari rebellions in many parts of northern and western India added to these problems. These revolts were sometimes caused by the pressures of mounting taxes. At other times they were attempts by powerful chieftains to consolidate their own positions. Mughal authority had been challenged by rebellious groups in the past as well. But these groups were now able to seize the economic resources of the region to consolidate their positions. The Mughal emperors after Aurangzeb were unable to arrest the gradual shifting of political and economic authority into the hands of provincial governors, local chieftains and other groups.

Rich harvests and empty coffers

The following is a contemporary writer’s account of the financial bankruptcy of the empire:

The great lords are helpless and impoverished. Their peasants raise two crops a year, but their lords see nothing of either, and their agents on the spot are virtual prisoners in the peasants’ hands, like a peasant kept in his creditor’s house until he can pay his debt. So complete is the collapse of all order and administration that though the peasant reaps a harvest of gold, his lord does not see so much as a wisp of straw. How then can the lord keep the armed force he should? How can he pay the soldiers who should go before him when he goes out, or the horsemen who should ride behind him?

In the midst of this economic and political crisis, the ruler of Iran, Nadir Shah, sacked and plundered the city of Delhi in 1739 and took away immense amounts of wealth. This invasion was followed by a series of plundering raids by the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali, who invaded north India five times between 1748 and 1761.

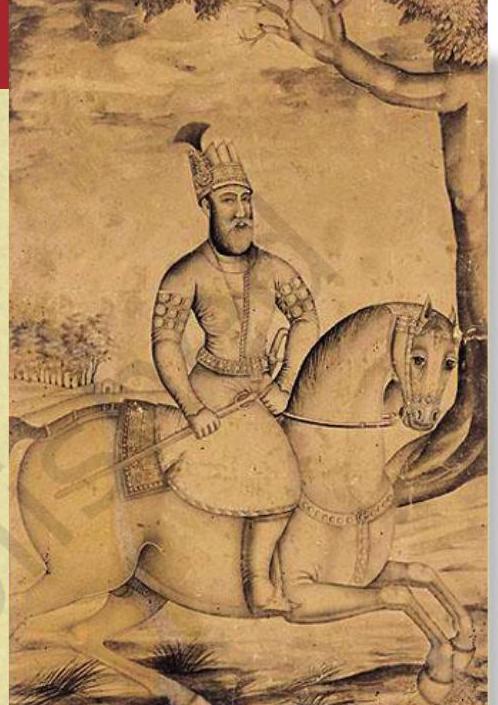

Nadir Shah attacks Delhi

The devastation of Delhi after Nadir Shah’s invasion was described by contemporary observers. One described the wealth looted from the Mughal treasury as follows: sixty lakhs of rupees and some thousand gold coins, nearly one crore worth of gold-ware, nearly fifty crores worth of jewels, most of them unrivalled in the world, and the above included the Peacock throne.

Fig. 1 A 1779 portrait of Nadir Shah.

Another account described the invasion’s impact upon Delhi:

(those) … who had been masters were now in dire straits; and those who had been revered couldn’t even (get water to) quench their thirst. The recluses were pulled out of their corners. The wealthy were turned into beggars. Those who once set the style in clothes now went naked; and those who owned property were now homeless … The New City (Shahjahanabad) was turned into rubble. (Nadir Shah) then attacked the Old quarters of the city and destroyed a whole world that existed there…

Already under severe pressure from all sides, the empire was further weakened by competition amongst different groups of nobles. They were divided into two major groups or factions, the Iranis and Turanis (nobles of Turkish descent). For a long time, the later Mughal emperors were puppets in the hands of either

Fig. 2 Farrukh Siyar receiving a noble in court.

one or the other of these two powerful groups. The worst possible humiliation came when two Mughal emperors, Farrukh Siyar (1713-1719) and Alamgir II (1754-1759) were assassinated, and two others, Ahmad Shah (1748-1754) and Shah Alam II (1759-1816) were blinded by their nobles.

With the decline in the authority of the Mughal emperors, the governors of large provinces, subadars, and the great zamindars consolidated their authority in different parts of the subcontinent, such as Awadh, Bengal and Hyderabad.

The Rajputs

Many Rajput kings, particularly those belonging to Amber and Jodhpur, had served under the Mughals with distinction. In exchange, they were permitted to enjoy considerable autonomy in their watan jagirs. In the eighteenth century, these rulers now attempted to extend their control over adjacent regions. Ajit Singh, the ruler of Jodhpur, was also involved in the factional politics at the Mughal court.

Many Rajput rulers had accepted the suzerainty of the Mughals but Mewar was the only Rajput state which defied Mughal authority. Rana Pratap ascended the throne at Mewar in 1572, with Udaipur and large part of Mewar under his control. A series of envoys were sent to the Rana to persuade him to accept Mughal suzerainty, but he stood his ground.

These influential Rajput families claimed the subadari of the rich provinces of Gujarat and Malwa. Raja Ajit Singh of Jodhpur held the governorship of Gujarat and Sawai Raja Jai Singh of Amber was the governor of Malwa. These offices were renewed by Emperor Jahandar Shah in 1713. They also tried to extend their territories by seizing portions of imperial territories neighbouring their watans. Nagaur was conquered and annexed to the house of Jodhpur, while Amber seized large portions of Bundi. Sawai Raja Jai Singh founded his new capital at Jaipur and was given the subadari of Agra in 1722. Maratha campaigns into Rajasthan from the 1740 s put severe pressure on these principalities and checked their further expansion.

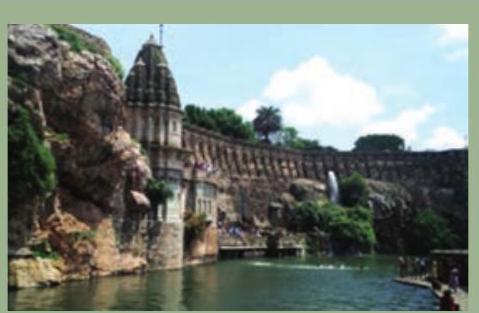

Many Rajput chieftains built a number offorts on hill tops which became the centres of power. With extensive fortifications, these majestic structures housed urban centres, palaces, temples, trading centres, water harvesting structures and other

Fig. 3 Chittorgarh Fort, Rajasthan buildings.

The Chittorgarh fort contained many water bodies varying from talabs (ponds) to kundis (wells), baolis (stepwells), etc.

Fig. 4 Jantar Mantar in Jaipur

Raja Jai Singh of Jaipur

A description of Raja Jai Singh in a Persian account of 1732:

Raja Jai Singh was at the height of his power. He was the governor of Agra for 12 years and of Malwa for 5 or 6 years. He possessed a large army, artillery and great wealth. His sway extended from Delhi to the banks of the Narmada.

Fig. 5 Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

Sawai Jai Singh, the ruler of Amber constructed five astronomical observatories, one each in Delhi, Jaipur, Ujjain, Mathura and Varanasi. Commonly known as Jantar Mantar, these observatories had various instruments to study heavenly bodies.

Fig. 6 Sword of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

What is the Khalsa?

Do you recall reading about it in Chapter 6?

Seizing Independence

The Sikhs

The organisation of the Sikhs into a political community during the seventeenth century (see Chapter 6) helped in regional state-building in the Punjab. Several battles were fought by Guru Gobind Singh against the Rajput and Mughal rulers, both before and after the institution of the Khalsa in 1699. After his death in 1708, the Khalsa rose in revolt against the Mughal authority under Banda Bahadur’s leadership, declared their sovereign rule by striking coins in the name of Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh, and established their own administration between the Sutlej and the Jamuna. Banda Bahadur was captured in 1715 and executed in 1716.

Under a number of able leaders in the eighteenth century, the Sikhs organised themselves into a number of bands called jathas, and later on misls. Their combined forces were known as the grand army (dal khalsa). The entire body used to meet at Amritsar at the time of Baisakhi and Diwali to take collective decisions known as “resolutions of the Guru (gurmatas)”. A system called rakhi was introduced, offering protection to cultivators on the payment of a tax of 20 per cent of the produce.

Guru Gobind Singh had inspired the Khalsa with the belief that their destiny was to rule (raj karega khalsa). Their well-knit organisation enabled them to put up a successful resistance to the Mughal governors first and then to Ahmad Shah Abdali who had seized the rich province of the Punjab and the Sarkar of Sirhind from the Mughals. The Khalsa declared their sovereign rule by striking their own coin again in 1765. Significantly, this coin bore the same inscription as the one on the orders issued by the Khalsa in the time of Banda Bahadur.

The Sikh territories in the late eighteenth century extended from the Indus to the Jamuna but they were divided under different rulers. One of them, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, reunited these groups and established his capital at Lahore in 1799.

The Marathas

The Maratha kingdom was another powerful regional kingdom to arise out of a sustained opposition to Mughal rule. Shivaji (1627-1680) carved out a stable kingdom with the support of powerful warrior families (deshmukhs). Groups of highly mobile, peasantpastoralists (kunbis) provided the backbone of the Maratha army. Shivaji used these forces to challenge the Mughals in the peninsula. After Shivaji’s death, effective power in the Maratha state was wielded by a family of Chitpavan Brahmanas who served Shivaji’s successors as Peshwa (or principal minister). Poona became the capital of the Maratha kingdom.

Fig. 7 Portrait of Shivaji

Towards the end of the 17 th century, a powerful state started emerging in the Deccan under the leadership of Shivaji which finally led to the establishment of the Maratha state. Shivaji was born to Shahji and Jija Bai at Shivneri in 1630. Under the guidance of his mother and his guardian Dada Konddev, Shivaji embarked on a career of conquest at a young age. The occupation of Javli made him the undisputed leader of the Mavala highlands which paved the way for further expansion. His exploits against the forces of Bijapur and the Mughals made him a legendary figure. He often resorted to guerrilla warfare against his opponents. By introducing an efficient administrative system supported by a revenue collection method based on chauth and sardeshmukhi, he laid the foundations of $a$ strong Maratha state.

Under the Peshwas, the Marathas developed a very successful military organisation. Their success lay in bypassing the fortified areas of the Mughals, by raiding cities and by engaging Mughal armies in areas where their supply lines and reinforcements could be easily disturbed.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj (1630-1680)

Chhatrapati Sambhaji (1681-1689)

Chhatrapati Rajaram (1689-1700 )

Maharani Tarabai (1700-1761)

Shahu Maharaj (Son of Sambhaji) (1682-1749)

Source: R. C. Majumdar, 2007. The Mughal Empire, Mumbai.

Baji Rao I, also known as Baji Rao Ballal was the son of Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath. He was a great Maratha general who is credited to have expanded the Maratha kingdom beyond the Vindhyas and is known for his military campaigns against Malwa, Bundelkhand, Gujarat and the Portugese.

Between 1720 and 1761, the Maratha empire expanded. It gradually chipped away at the authority of the Mughal Empire. Malwa and Gujarat were seized from the Mughals by the 1720s. By the 1730s, the Maratha king was recognised as the overlord of the entire Deccan peninsula. He possessed the right to levy chauth and sardeshmukhi in the entire region.

Chauth

25 per cent of the land revenue claimed by zamindars. In the Deccan, this was collected by the Marathas.

Sardeshmukhi

9-10 per cent of the land revenue paid to the head revenue collector in the Deccan.

After raiding Delhi in 1737, the frontiers of Maratha domination expanded rapidly: into Rajasthan and the Punjab in the north; into Bengal and Orissa in the east; and into Karnataka and the Tamil and Telugu countries in the South (see Map 1). These were not formally included in the Maratha empire, but were made to pay tribute as a way of accepting Maratha sovereignty. Expansion brought enormous resources, but it came at a price. These military campaigns also made other rulers hostile towards the Marathas. As a result, they were not inclined to support the Marathas during the third battle of Panipat in 1761.

Alongside endless military campaigns, the Marathas developed an effective administrative system as well. Once conquest had been completed and Maratha rule was secure, revenue demands were gradually introduced taking local conditions into account. Agriculture was encouraged and trade revived. This allowed Maratha chiefs (sardars) like Sindhia of Gwalior, Gaekwad of Baroda and Bhonsle of Nagpur the resources to raise powerful armies. Maratha campaigns into Malwa in the 1720 s did not challenge the growth and prosperity of the cities in the region. Ujjain expanded under Sindhia’s patronage and Indore under Holkar’s. By all accounts, these cities were large and prosperous and functioned as important commercial and cultural centres. New trade routes emerged within the areas controlled by the Marathas. The silk produced in the Chanderi region now found a new outlet in Poona, the Maratha capital. Burhanpur which had earlier participated in the trade between Agra and Surat now expanded its hinterland to include Poona and Nagpur in the South and Lucknow and Allahabad in the East.

The Jats

Like the other states, the Jats consolidated their power during the late seventeenth and eighteenth-centuries. Under their leader, Churaman, they acquired control over territories situated to the west of the city of Delhi, and by the 1680s, they had begun dominating the region between the two imperial cities of Delhi and Agra. For a while, they became the virtual custodians of the city of Agra.

The power of the Jats reached its zenith under Suraj Mal who consolidated the Jat state at Bharatpur (in present day Rajasthan) during 1756-1763. The areas under the political control of Suraj Mal broadly included parts of modern eastern Rajasthan, southern Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and Delhi. Suraj Mal built a number of forts and palaces and the famous Lohagarh fort in Bharatpur is regarded as one of the strongest forts built in this region.

The Jats were prosperous agriculturists, and towns like Panipat and Ballabhgarh became important trading centres in the areas dominated by them. Under Suraj Mal the kingdom of Bharatpur emerged as a strong state. When Nadir Shah sacked Delhi in 1739, many of the city’s notables took refuge there. His son Jawahir Shah had 30,000 troops of his own and hired another 20,000 Maratha and 15,000 Sikh troops to fight the Mughals.

While the Bharatpur fort was built in a fairly traditional style, at Dig the Jats built an elaborate garden palace combining styles seen at Amber and Agra. Its buildings were modelled on architectural forms first associated with royalty under Shah Jahan.

Fig. 8 Eighteenth-century palace complex at Dig. Note the “Bangla dome” on the assembly hall on the roof of the building.

Imagine

You are a ruler of an eighteenth-century kingdom. Tell us about the steps you would take to make your position strong in your province, and what opposition or problems you might face while doing so.

Keywords

subadari

dal khalsa

misl

faujdari

ijaradari

chauth

sardeshmukhi

Let’s recall

1. State whether true or false:

(a) Nadir Shah invaded Bengal.

(b) Sawai Raja Jai Singh was the ruler of Indore.

(c) Guru Gobind Singh was the tenth Guru of the Sikhs.

(d) Poona became the capital of the Marathas in the eighteenth century.

Let’s discuss

2. How were the Sikhs organised in the eighteenth century?

3. Why did the Marathas want to expand beyond the Deccan?

4. Do you think merchants and bankers today have the kind of influence they had in the eighteenth century?

5. Did any of the kingdoms mentioned in this chapter develop in your state? If so, in what ways do you think life in the state would have been different in the eighteenth century from what it is in the twenty-first century?

Let’s do

6. Collect popular tales about-rulers from any one of the following groups of people: the Rajputs, Jats, Sikhs or Marathas.